Studio Visit: Cy Gavin

Cy Gavin is a visual artist born and raised in western Pennsylvania, whose work often explores themes of the African diaspora and his family’s heritage on the islands of Bermuda and Puerto Rico. In 2015, nearly six years after the death of his father, he went to Bermuda for the first time to explore the British Overseas Territory’s deep—if strangely obscured—relationship to the transatlantic slave trade. While there, he became engrossed with the shrouded and tense narrative of an elderly local rebel slave named Sally Bassett.

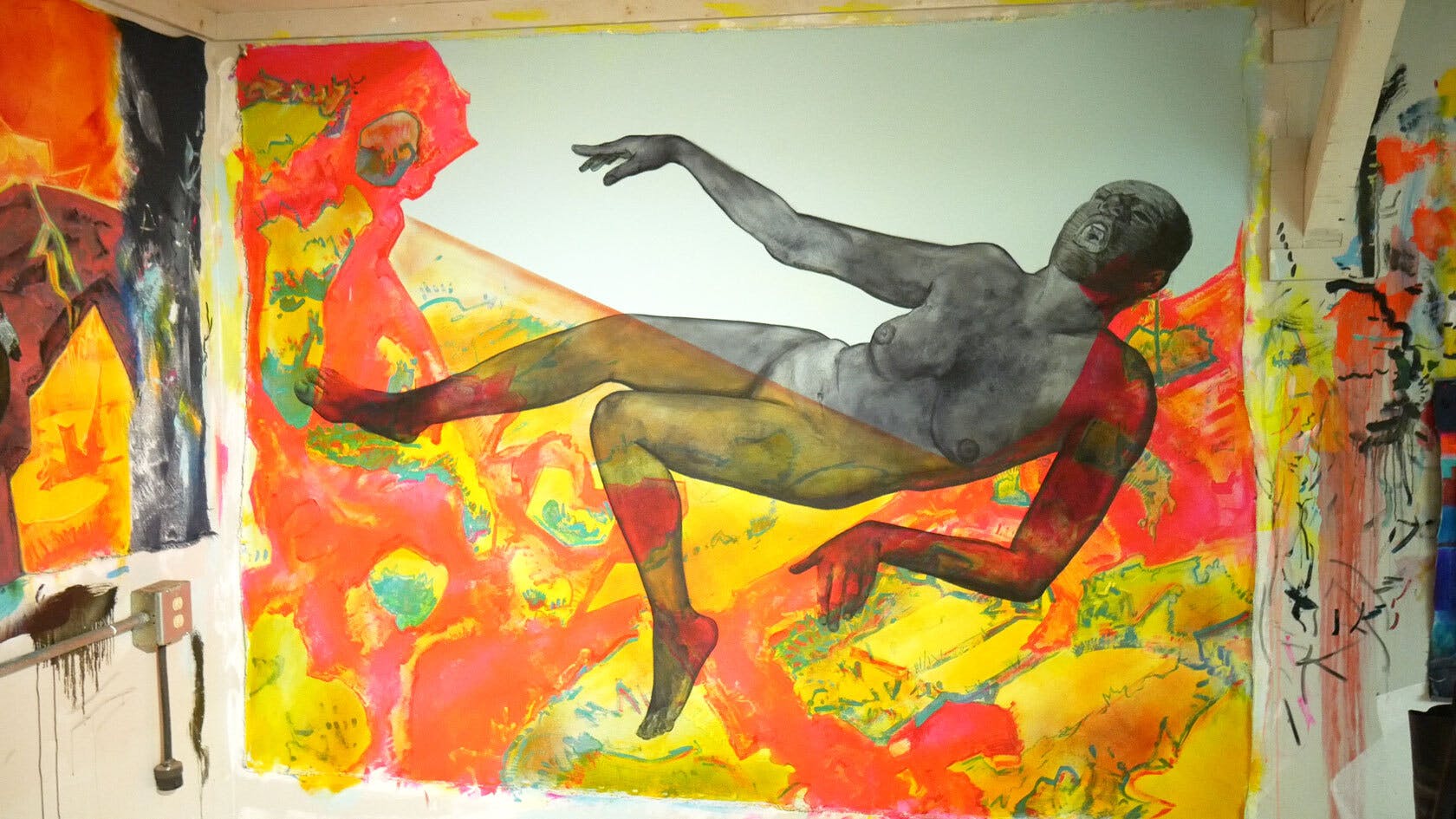

The artist now divides time between Washington Heights and a rural town two hours north of New York, where his studio is a converted barn on over a hundred acres of woodland. This November, Gavin is showing painting and sculpture at Various Small Fires in Los Angeles, and his first European solo show will take place in early 2018. In the diminishing May sunshine of a Saturday afternoon, Gavin discussed the ideas that animate his bright, beautiful work.

Alex Frank: Tell us about Sally Bassett, a central presence in your last series of paintings.

Cy Gavin: I’m interested in contested histories and how societies construct collective memory. Sally Bassett was arraigned for allegedly poisoning the family who owned her granddaughter; the master and mistress of the house and another slave were poisoned. She was accused of using ratsbane and manchineel root. She denied it. In very short order, the trial took place and she was found guilty. She was sentenced to burn at the stake. Officers paraded her down to where she was going to die, Crow Lane—a little park now. As she was brought down, she was cracking jokes to people who were rushing to see the execution. She said, “No use you hurrying folks. There’ll be no fun till I get there!”

I was fascinated by her making light of her situation. Interestingly, her words were printed in the newspaper, which was rare for someone enslaved. As a consequence, word of her execution and her jokes made its way to the Bahamas and other colonies, which then experienced insurrections. They had taken inspiration from Sally Bassett’s unbothered attitude. She became a folk hero and an unwitting catalyst for revolution.

AF: There was a controversy just a few years ago, when a local artist wanted to erect a statue of her in Bermuda.

CG: Many people are afraid of talking about her; they want her to go away. There is a resurgent interest in Sally Bassett because of a monumental sculpture by the artist Carlos Dowling. The statue was meant to be shown prominently outside of City Hall in the capitol, Hamilton. Amid protests and attempts to censor the work, it was relocated to the outskirts of the city. The fact that Sally Bassett’s story survived is incredible, and to have people still trying to suppress its existence irritates me. I’m drawn to figures that don’t even have an image of them. I’m attracted to thwarting the efforts to eradicate the narratives of these people, which have somehow survived against all odds.

AF: Why do you think discussing Bassett is so taboo in Bermuda?

CG: Dowling’s sculpture brought about a conversation that for many was a reminder that Sally Bassett’s actions are still seen as inciting and dangerous in their implications—they direct attention to contemporary social issues that stratify society along the lines of race and class. Bermuda’s tourism enterprises have created an image of Bermuda as a paradise of leisure, in the most Anglo-Saxon terms possible. That image was first created in the 1920s, when to create golf courses, resorts and a railway, the government used eminent domain to seize huge tracts of land that had been allocated to emancipated slaves. Tucker’s Town was the name of the district and it was a flourishing community with schools, churches, farms and Black-owned businesses. The community was razed to the ground and its people expropriated and shunted off to provisional housing in the margins of other parishes.

Because sites of leisure were built atop a community, it happened that a luxury resort, Rosewood Tucker’s Point, was built around the community’s cemetery. It was one of the few remaining traces of that community. In October 2012, the resort surreptitiously bulldozed all of these graves in an apparent effort to erase history.

Sally’s image is a reminder of how systems that have subjugated Black people in Bermuda have endured, in changed form, through the modern era. When the statue entered a present-day dialogue, it shared headlines with flagrant reminders of contemporary institutional racism. She was a touchstone by which people could measure progress. Discussions of her are incongruous with the myth of Bermuda being paradise.

AF: Do you have a connection to Tucker’s Town?

CG: Tucker’s Town happens to be where my great-grandparents, Nellie DeCosta Smith and Lewis Smith, lived. I am related to the last remaining resident, who was forcibly removed, Dinna Smith. My father grew up with Nellie. He would dreamily recount leaving the slums with his friends and going to Hamilton Harbor as a teenager, where the cruise ships moored. He and his friends would collect the lobsters that were discarded from the cruise ships. They felt really lucky, but were literally eating someone’s trash. My work is questioning these social structures, not really attempting to answer to them.

AF: You use bold colors, such as orange, yellow and pink. How’d you come to them?

CG: I think that my colors can be strident, but I also think you can use strident things with subtlety. That’s what I’m trying to do. It’s hyperbolic in the way of caricature, which can feel closer to the truth by being an exaggeration.

AF: You used your father’s cremated remains in Portrait of My Father (2015). Tell me about that process.

CG: I had been thinking about how a painting can be seen as a time capsule, or in this case a reliquary. My sister had mentioned returning my father’s ashes to Bermuda. In several paintings I incorporated his remains into the paint along with pink sand from Bermuda. Rather than some kind of memorial, I was really placing those materials next to one another to consider their sameness.

I was preoccupied by the culturally assigned value of a body, and how that value varies in societies depending on what your body looks like. I was thinking about the countless Black bodies who would have been thrown into the Atlantic off of the shores of Bermuda (the archipelago was used as a way-station for shipsbearing slaves from Africa to the New World) and how their bodies would have entered the environment quite literally. I was thinking about the frailty of the human body and how the same periodic elements that constitute our bodies compose our environment, from concrete of a city to pink sand beaches.

AF: Why paint on denim instead of canvas?

CG: I was in Charleston, South Carolina, and visited the Old Slave Mart Museum. Until then, I hadn’t understood how indigo had been such an important cash crop for South Carolina. It was second to rice. Like rice, indigo was cultivated in West Africa, so people had the skills to grow it already. In terms of climate, parts of West Africa are similar to the Sea Islands of South Carolina. I was struck by how a color could be so important—it was used as currency when the dollar was floundering, as cakes of indigo. It was what they used for the blue of the first American flag. I was also drawn to denim being used as a working person’s material. Denim is the history of American indigo married with the history of American cotton in one material.

AF: What are you currently working on?

CG: At the moment, I’m focusing on my first European solo show, which will take place in the Spring of 2018 at VNH Gallery in Paris. Before that, though, I’m excited to show new work in group shows in New York at Callicoon Fine Arts and JTT, respectively. And this fall I’ll be showing painting and sculpture in Los Angeles at Various Small Fires.

AF: With your new work and painting historical slave figures such as Bassett, what feelings are you hoping to inspire in the viewer?

CG: I see her as an entry point to think about dignity and the refusal of meekness. Particularly at a moment when it seems like ignorance is being mobilized to subjugate people—still. I’m convinced of that because of the conflict about Carlos Dowling’s statue. I’m convinced of that when Rosewood Tucker’s Point felt the need to quietly destroy Marsden Church Cemetery in 2012 and I’m convinced of that when I see scant evidence of even the existence of Black people at the historical society today. These machinations keep Black people in a place of invisibility. There’s a reason these narratives survive. I think they’re a cautionary point. Even if it is a myth, it doesn’t matter, because it’s done something.