Possessions: Sadie Barnette and Leslie Hewitt

I want to make sure we’re all on the same page.

possess (v.)

late-14c., possessen, “to hold, occupy, inhabit” (without regard to ownership), a back formation from possession and in part from Old French possesser “to have and hold, take, be in possession of” (mid-13c.), from Latin possessus, past participle of possidere “to have and hold, hold in one’s control, be master of, own,” probably a compound of potis “having power, powerful, able” (from PIE root *poti- “powerful; lord”) + sedere, from PIE root *sed- (1) “to sit.”

According to Buck, Latin possidere was a legal term first used in connection with real estate. The meaning “to hold as property” in English is recorded from c. 1500. That of “to seize, take possession of” is from 1520s; the demonic sense of “have complete power or mastery over, control” is recorded from 1530s (implied in possessed); the weakened sense of “fascinate, enthrall, affect or influence intensely” is by 1590s.1

With this, let’s think about possession expansively. Etymology reveals a word’s shifting meaning. Possession is all we’re able to hold and live inside of. It’s property, the ability to take something as yours. To be possessed is to be filled with feeling, under the influence of something more powerful than yourself. Leslie Hewitt’s series “Riffs on Real Time” and Sadie Barnette’s series of untitled drawings invite the viewer to think about all they might possess and all that might in turn possess them. Their work isn’t a simple tallying up of assets. Instead, they’re steeped in care, finding value in photos, ephemera, and relationships—possession of a different kind of inheritance, a different kind of wealth.

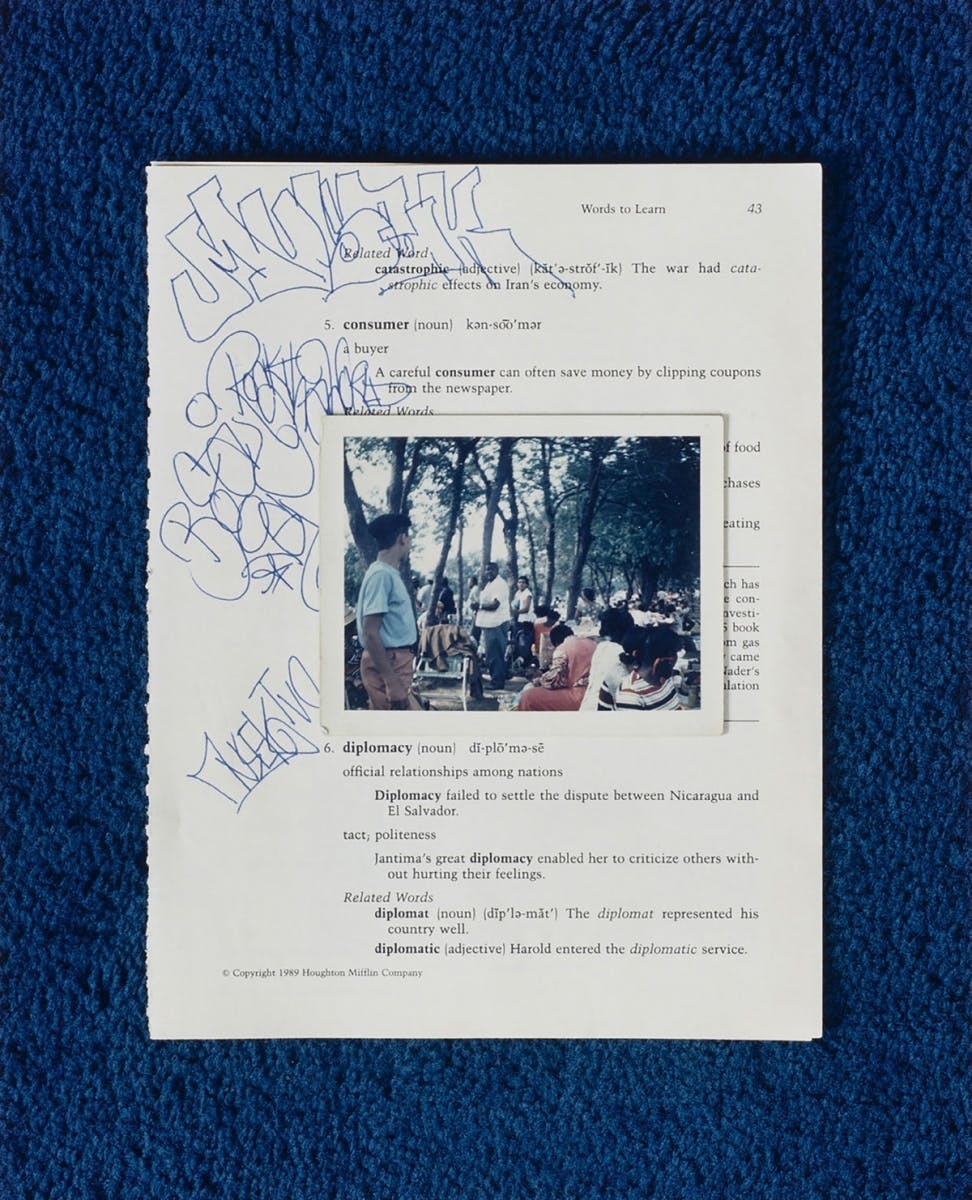

In the photographic series “Riffs on Real Time,” Hewitt composes sparse still lifes. Each image can be read in three layers. First: a setting of colorful carpet or hardwood flooring that place us in a home. Second: a piece of printed material, from a worn book to a single pulled-out page. These are not new objects, and each is made to feel precious by the merit of having been kept and cared for. Third: a candid photograph at the top of the pile.

This series was inspired by Hewitt’s interest in her grandmother’s arrangement of family photos in albums with “total disregard for chronology or linear time.”2 The images in “Riffs on Real Time” maintain the tone of a family archive, but the mix of photos with more common printed matter situate personal histories in the context of larger cultural moments. Hewitt’s images feel both specific—these are someone’s possessions, someone’s heirlooms—and deeply familiar—these are our heirlooms.

As I wrote this, I moved around my apartment making mental lists of heirlooms. I can make small arrangements of my own. The work also prompted me to think about all the heirlooms I wish I had—places of dispossession. The photos and objects that didn’t make it to this moment right now. What was it that no one thought to save, that fell apart, that got lost along the way? Anyone who has moved understands the heft of their earthly possessions and how this loss happens. We can only keep so many heirlooms before they become a burden, only for their mass and the responsibility they carry.

In this way, however, heirlooms also anchor. Their weight can fix you in place in a long line of family and archivists. Hewitt’s work conjures the prospects of a collective archive that moves beyond the bounds of biological family. I want to rely on one of the roots of to possess: to inhabit without regard to ownership. This is a case of usufruct: we can exercise the right to make use, benefit, and enjoy another’s possessions or property so long as the person making use causes no damage.3 I want to imagine a way inside Hewitt’s images, held in place by something there too. Even if the objects aren’t mine, how can I also care for them?

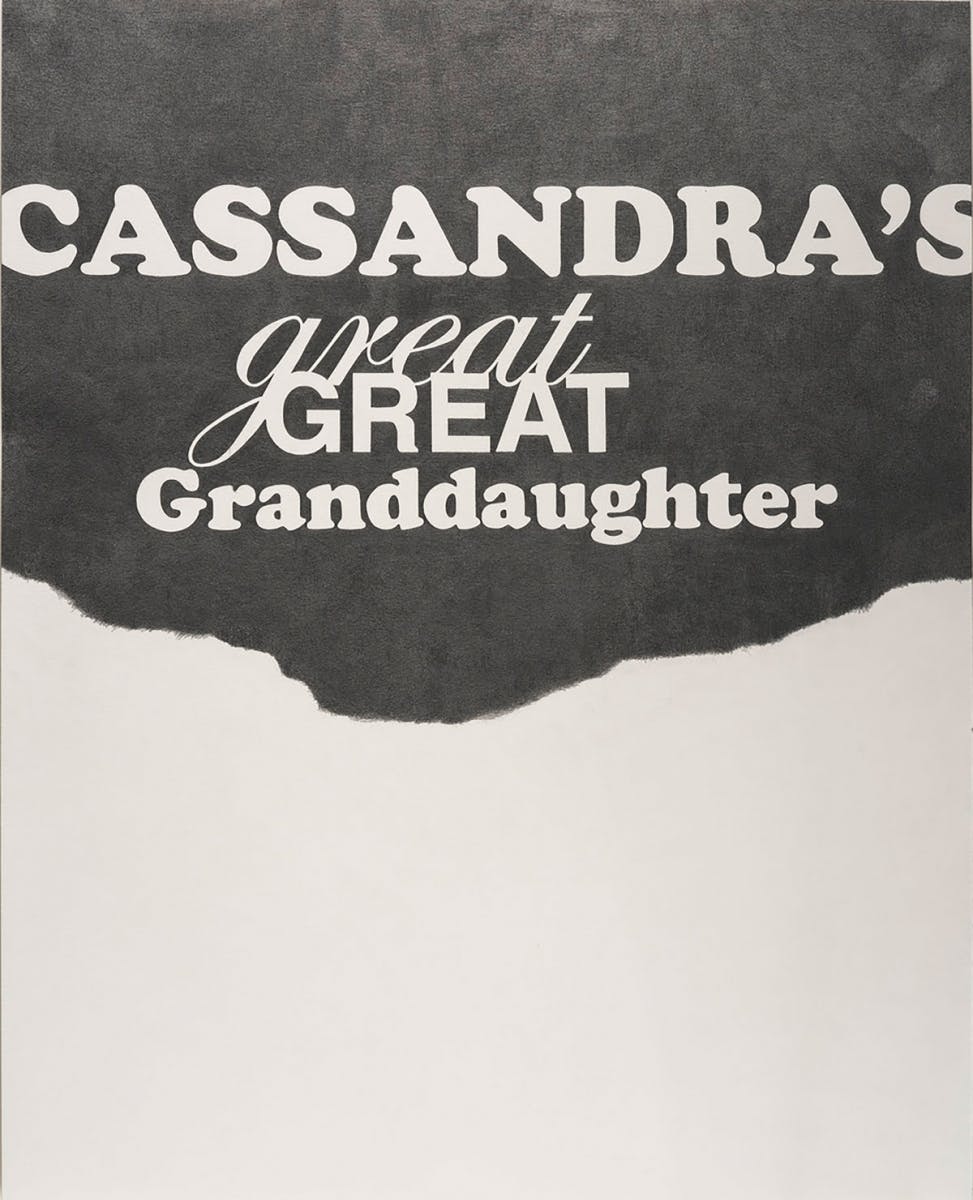

In a group of works, all Untitled, Sadie Barnette sketches a family portrait using only text. Each piece outlines a particular relation:

Cassandra’s Great Great

Granddaughter

Great Granddaughter of Agnes &

Samual

Uncle Rodney’s Daughter

Luverne & Sadie’s Granddaughter

Little Rodney’s Little Sister

Youngest Niece of: Margaret, Vivian,

Luverne, Stanley, Carl, Aubrey, Alvin,

Lesley, Irwin and John

Strikingly minimal, we come to see loved ones live in parts of speech. There is tenderness in the apostrophe. It’s a possessive, meant to have and hold. These small marks flow in two directions, a mutual embrace where they are mine and I am theirs. Of indicates a point of origin, relates a part to a whole, describes belonging to.4 Suddenly of is shorthand for all the work done by a family tree. It’s also a preposition, the place where we figure out how two things are related. Of leads to stories that can talk about from, with, among, beside, and around. The colon in “Youngest Niece of:,” a tool for situating elements inside of a list, becomes a way to stage a gathering of relatives. Barnette’s works thus point us toward a grammar of relation.

While Barnette centers her work around immediate family in these drawings, the form, like Hewitt’s, again feels easy to slide into. Grammar is a tool for all who share the language. It can also expand to encompass a broader, chosen family. I want to propose: ________’s oldest friend The emergency contact of ______________ The roommate of: __________, ________, _________ and __________ ___________’s shoulder to cry on Caretaker of ____________ ____________’s dance partner Close, personal friend of ____________ ____________’s coconspirator Barnette begins her family tree with Cassandra. The artist shares, “She’s as far back as we trace our family on my father’s side … My dad did a lot of family research—that’s why we have these giant, 500-person family reunions every two years (where) everyone who is there is a descendant of Cassandra.… The story goes she was a Cherokee woman who escaped from enslavement.”5 To be the root of a family tree is to possess everyone who follows. Though Barnette’s drawing highlights “Cassandra’s Great Great Granddaughter,” everyone at her family reunion is Cassandra’s, full stop. Barnette points to her legacy’s effect on the family. Here possession shifts again: to fascinate, enthrall, or influence intensely. It’s a wonder to think about being the exponentially great granddaughter of family once known. I’m sure I would be just as much a marvel to them. Once again, the way we hold each other goes both ways.

Together, Hewitt’s work focuses on what you might possess, and Sadie Barnette’s work focuses on what might possess you. Both bodies of work find strength in holding on to the past, the objects, and people who have come before us. The Latin root of possess, possessus, a past participle of possidere, is most likely a compound of potis meaning “having power, powerful, able” and sedere meaning “to sit.” Hewitt and Barnette’s work concludes that to sit in power is to sit alongside family, past and present. The idea of self-possession is undone. In talking about her work Barnette has said, “I’ve always felt like it’s some people’s job to take care of the future … For whatever reason I feel like it’s my job to take care of the past.”6 Take care of the past and it will take care of you too.

Notes

1) Douglas Harper, “Etymology of possess,” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed February 20, 2023, etymonline.com/word/possess.

2) Whitfield Lovell, “Leslie Hewitt,” BOMB, July 1, 2008, bombmagazine.org/articles/leslie-hewitt/.

3) “Usufruct,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, October 2021, law.cornell.edu/wex/usufruct.

4) Merriam-Webster, s.v. “of,” accessed March 7, 2023, merriam-webster.com/dictionary/of.

5) Tony Bravo, “Sadie Barnette’s Solo Exhibition Makes Art from Family Legacies,” Datebook, San Francisco Chronicle, December 9, 2021.

6) Tony Bravo, “Sadie Barnette’s Solo Exhibition Makes Art from Family Legacies.”