Partners in Conversation: Kahmia Moise

Partners in Conversation is an interview series that highlights the Studio Museum’s partnership educators, school leadership, artists, and community organization staff. These interviews seek to document and archive their experiences and to share their stories—in their own words—of connecting to the Studio Museum, Harlem, and artists of African descent. This act of documenting their voices intends to honor the unquantifiable role Studio Museum partnerships played in the founding and history of Studio Museum, as well as the central role they will continue to play in shaping the Museum as it moves into the future. These interviews intend to shine a light on the creativity and innovation our partners cultivate in their schools, organizations, and in Harlem, and acknowledge that the collaborative work we do together is one small part of a much larger ecosystem. The Studio Museum works in support of and in collaboration with individuals who infuse their spaces with creativity every day.

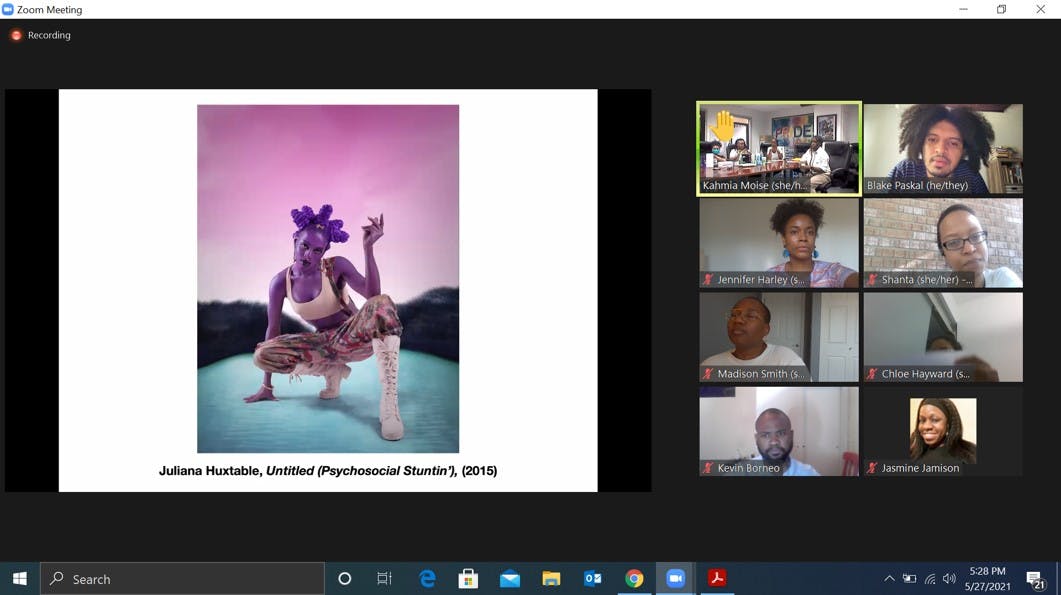

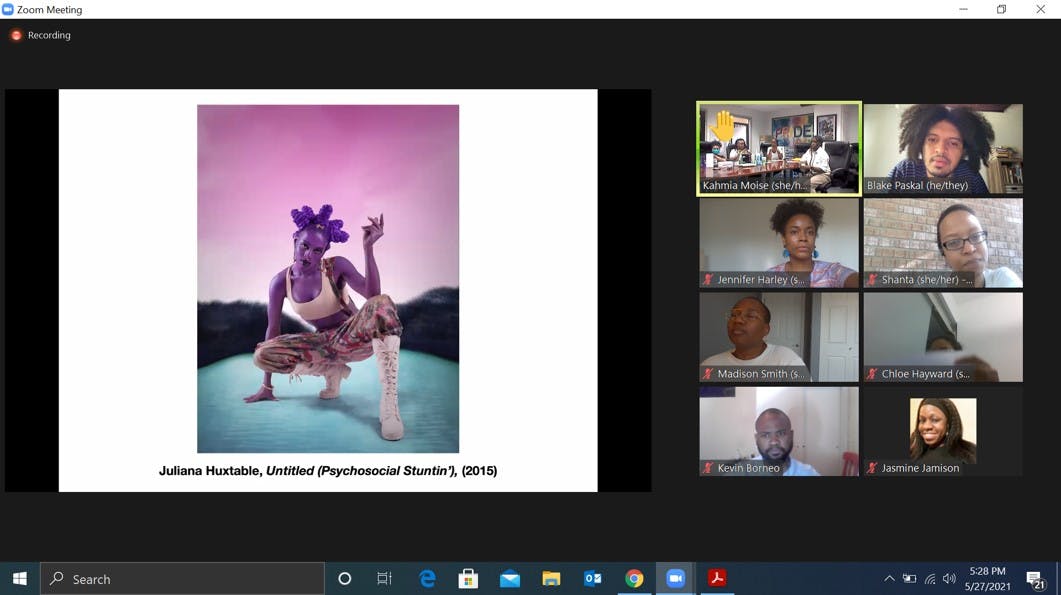

In this Partners in Conversation, Studio Museum School & Community Partnership Manager Jennifer Harley speaks with Kahmia Moise, a long-time staff member at the Ali Forney Drop-In Center in Harlem, about art making as a path toward justice, cultivating community care, the challenges of reimagining organizational structures, and queer community building in Harlem.

Jennifer Harley: I want to start with your background. Where did you grow up?

Kahmia Moise: I was, raised, and currently reside in Jamaica, Queens, not too far away from JFK airport. I live with my mom, younger sister, and partner in our family home.

JH: I know you studied English, specifically writing, as an undergraduate. What role did creativity play in your life as a young person?

KM: Creativity provided an outlet for all of the thoughts, questions, and observations going through my mind. It also provided the opportunity to practice liberation through freedom of speech and expression and creative licensing. Writing and being creative in that way was also a therapeutic practice for me. It assisted me with critical thinking and challenging norms.

JH: Tell me more about your experience as a young person. Were there specific people, educators, or community organizations who supported you?

KM: As both a young person and a creative person I felt most seen and supported throughout my high school. The school was very small. Our principal and assistant principal were both Black women; they were pillars of the school and they made a great impact. They supported and invested in us and the teachers and community members invested in our growth. I write a lot of poetry and I wrote my first real poem in high school. I wrote it, performed it, and shared it with folks. That helped me do those sorts of things in college.

JH: Are you working on anything you are open to speaking about? What are you most energized by in your own practice?

KM: I write as a self-care practice usually. My writing most often reflects me being in conversation with people I am unable to converse with at that moment in time or never again in the future.

JH: Ali Forney Center (AFC) is an organization founded in the memory of Ali Forney, a houseless and queer young person who was murdered in Harlem. As an organization, you focus on supporting houseless LGBTQIA+ young people. I’m excited to learn more about how you came to do work in community-focused spaces.

KM: After graduating, I didn’t know what I wanted or needed to do. I started working at the DC Center, which is similar to our LGBT Center in NY. What attracted me [to the DC Center] was their queer community, but that space was also very white. When I came back to New York City to job search, I came across AFC, which was another LGBTQIA+ space. It’s not really how I got there, I was just fresh out of undergrad and applying to jobs and I wanted a new experience. But what really kept me here is being able to build community, be part of a community that I didn’t know existed, and not only be a part of the community but support the community as well. The youth who are experiencing homelessness, the staff who identify in many ways with the youth, how I am able to support them, how they are able to support me, that exchange of love, respect, healing, and care is what has kept me in this work for as long as I have been in it.

JH: How long have you been at AFC?

KM: Since 2015.

JH: What are some of those things that still make you excited to come back to this work every day?

KM: I work on a team where I am a leader but I don't always have to lead. There’s a lot of collaboration happening that I look forward to in the day-to-day and that collaboration involves taking care of one another in different ways.

JH: We started our partnership in 2019 with a sculpture project that asked participants to create a figurative bust of someone they wanted to memorialize. In that moment, we were thinking specifically about the murders of many trans and gender-nonconforming individuals. I know memorials have taken on new weight over the past few years and we have been in conversation recently about how we can again think about memorials in the aftermath of the pandemic. How do you think art can help people process trauma?

KM: Art helps me process trauma by giving me an opportunity to express and articulate emotion freely, on my terms, without having to fit any particular standard. It allows me to look back at a moment and reflect. To show progression, evolution, and to understand where I am and where I've come from, and perhaps, where I want to go.

JH: What is your why—why do you do this work, and why is it important to you?

KM: People really depend on me, I show up as a huge support to a lot of people, I am some sort of comfort or sense of safety for folks. My why is to help people find that [voice] and activate it within themselves. Until we get to a place where we all feel as though what we're bringing is wanted and that there's space for it.

JH: In your time at the organization, I know you started as a Residential Youth Counselor. Can you talk about what that role entailed? Does that role continue to inform the work you do at AFC?

KM: That was my introduction to AFC. I was on call. I spent between twenty to thirty hours a week directly working at the residential sites. I used to work the six to ten pm shift. Back in 2015, our residential sites were not [yet] open 24/7. I would be responsible for opening up the site in the evening, cooking dinner, assisting with chores for the night, and engaging with the youth on a personal level because you are in a home setting with them.

It’s special to experience working by yourself with six to twenty youth in a close setting. In my work now I have to be mindful of how I can connect those dots, how can I connect housing and drop-in, how can I connect admin and main office, how can we be more collaborative, and how can we build community across departments and programs? We have a new executive director who started in 2020. Last year was the first time we hired people who had worked significantly inside our program department in our main office, interacting with HR, with development. Before, none of the folks in [the admin] office had significant program experience but now four out of about six of us have, from being a youth counselor up and I feel like that is very great. It gives a huge perspective, understanding, and context.

JH: It’s always great to see people in institutional leadership positions with firsthand experience in programs and community work. AFC provides a wide array of resources and programming: housing, meals, health and mental healthcare, education, job training, and so much more, but I know the arts are often a large part of what you all do. Why do you think access to the arts is important for the young people who are a part of AFC's community?

KM: Access to the arts provides our youth and our larger community alternate ways of expressing, healing, and articulating themselves. [Art helps us] understand the obstacles that are present and what is needed to push forward. Our access to the arts now is way different from the way it was when I first started. Now we have our [Studio Museum] partnership. Linda created an arts programming department in 2017. Did you work with Linda?

JH: Yes, when we first started our conversations I was mostly collaborating with the wonderful artist and former AFC staff member Linda LaBeija before we got connected.

KM: Linda did a lot to expand art programs at AFC, work that Glitter Parsigian continued with the Creative Arts Therapy program. It's still relatively new here, especially since we are celebrating our twentieth year this year. Before that, we would expect our youth to express themselves through therapy or case management and that was not always accessible. Access to the arts allows alternatives for folks to engage with each other, staff, the programs, and to have agency and engage with themselves. Art challenges traditional ways of expression.

JH: When I first connected with Linda in 2017 shortly after I started at Studio Museum, I worked with our education intern Jasmine Weber to connect to the schools and organizations close to us and that we had never worked with. I was thinking about Harlem community members, particularly young people whose experience of education spaces was nontraditional, interrupted, or happening outside of a K–12 school context, and about the long history of Black queer spaces in Harlem. At the time, there were no programs at Studio Museum that specifically centered queer and trans youth in Harlem. The Drop-In Center, located just a block and a half away from our museum on 125th Street was at the top of our list. How has Harlem, its community, history, and organizations influenced your work?

KM: I always think of Harlem as a Black, queer, art space. Thinking about the history, it was where so many queer people were in terms of arts, fashion, and Black excellence.

When I worked at the Drop-In Center, our staff vibe is family-like and collaborative, supportive; [we] have each other's backs. The work is always crisis work. It always felt heavy but it felt like we could get through it with each other and we trusted each other in getting through it. We’d use Harlem as a place to de-stress and hang out, get drinks, have dinner, dance. I worked in the Drop-In on 125th and I also went to Columbia’s School of Social Work so I mostly was in Harlem, hanging out with folks, having fun with folks, it was a great time and we are a bunch of queer and trans people together roaming the streets at night, sometimes being belligerent, sometimes running into clients, but always having fun, building and strengthening community. I don't know how it has influenced my work but Harlem took care of me after my workdays. Me and a coworker used to go to L Lounge on 116th and St. Nic after work every Thursday. It became a thing. Other coworkers would join us and I would also invite everybody to hang out in Riverbank State Park. Harlem was like our self-care. Our play. It helped us build and share community with each other and made us refreshed for the next day. Sometimes I would come the next day in the same clothes from the previous day but it is ok, because Harlem took care of us.

JH: Beautiful, you are creating new Black queer spaces in Harlem! There are so many Black artists and people who have always been amazing and queer in Harlem but historically many of their stories or their queerness has been erased. Uncovering and archiving more of these Black queer Harlem stories is something we’re doing more of with our Last Address Tribute Walk Harlem in collaboration with Visual AIDS. Why do you think collecting, exhibiting, and teaching with art by Black queer artists is important for a museum? How have AFC youth responded to those artists we talk about?

KM: Black queer representation in art is important for us and our youth. To be presented versions of us and our culture in the present and past, through different perspectives and mediums. To see ourselves in the future.

JH: We have collaborated with Studio Museum artist-educator Blake Paskal over the past four years of this partnership, visited Studio Museum exhibitions in Harlem, and made art in at the Drop-in Center and online. What has the experience been like having a queer artist of African descent be a part of your AFC community?

KM: The experience has been affirming, refreshing, and appreciated. It is great to work with family and community in these ways.

JH: When the new Studio Museum opens on 125th Street what are your dreams for the space?

KM: I hope that the space serves as a respite where clients and staff may escape and take a break from the Drop-In or their residential sites. Engage with the art and people of the museum, meet other community members, learn the history and current events, see themselves represented, feel welcomed and affirmed as well as inspired by the space, art, and people.

JH: I know you were instrumental in the founding of AFC’s Black Staff Affinity Group. What was the catalyst for forming the group? How has it been going?

KM: We brought in a racial equity consultant, she hosted a few focus groups for Black staff. From the focus groups, it was clear Black staff wanted a space to get together and provide support to each other, or just talk to each other. I was her co-facilitator and she asked for someone to take the group over and I took it over. As the facilitator, I would often experience anxiety leading up to the meetings, but after each meeting, I was so happy I was there; I was so happy I could hold the space for folks. It’s a support space, a space to check in, speak about what happened in the last week, and speak about what is on everyone’s minds.

JH: Belated congratulations on your new role as the Director of Equity and Inclusion! It’s a big thing to be done anywhere at any time but particularly at this moment when there have been so many organizations making shifts. How has it been to be a Black leader who is taking on this role?

KM: Thank you! I am coming up on a year in the role. Initially, even though I knew it was not the case, it did feel performative, staged to some degree. I have actually been involved with racial equity work with AFC since 2017. That was when it really started and it just [so] happened that in this moment in 2020 we had a change of leaders who made the choice to invest in this role and the building of this department.

It’s a lot of pressure being a Black person in this position. I think people expect a lot and I need to understand that not everyone is going to be satisfied at all times. I need to realize I can only do what I can do. I try to keep in mind that this work requires both patience and stamina. I hear from folks that there are not going to be results right away. That’s hard to hear, knowing the conditions of our staff, people are upset now, people are burnt out now, people are oppressed now. I’m one person in this role/department and I try to be as transparent as possible. I try to create a space where folks are able to come and speak to me and I let them know that they are not necessarily going to get a solution right away but I will work with them to get to that solution.

JH: It sounds like a collaborative process. Is collaboration one of the ways you are working to shape the systems?

KM: Yes, but there are still voices and people who are left out. The overall goal for me is that equity and inclusion are not separate from [each staff member’s] role but embedded in their role and work. The collaboration piece is a puzzle, but I like puzzles.

JH: When I first started in my role at Studio Museum, it took me a moment to realize how long this work really takes. I remember when Nico Wheadon, the former Director of Public Programs and Community Engagement, left the museum she mentioned that her five years in the role on a time scale of community-focused work was really just a moment. I remind myself of that frequently. Building relationships and collaboration is slow work, but there is beauty in that slowness. Collaborating with AFC has been such a teacher, our partnership over the years has required so many shifts and adaptations, it has taken on many different forms and formats, we have grown slowly together and our partnership is stronger for it. Houselessness continues to be a major challenge in New York City and throughout the country, particularly we know it affects Black and POC queer and trans young people disproportionately. How can we work collaboratively within our communities like Harlem to shift this, to create safe spaces?

KM: My coworker Naz challenges the idea that one can ever really create a safe space because the question is always: safe to whom? But we can create a brave space and I go back and forth with that in my head. The response I have is that we have to ask others: what do you need to be safe? Communities and individuals can do better at listening to people, understanding and believing their realities to not exacerbate or perpetuate experiences of harm in order to create brave and safer spaces for BIPOC, trans and queer people to thrive.

Community care, I think it is actually coming back in a strong way. And I think it is led by art. I think people have to have the will to take care of somebody and share space with them.

So, for example, this is a gift and a curse for me. I am really big on bringing people together and being among community and I think I got this from AFC. Similar to how we would hang out in Harlem, people are welcome at my house all the time. My house is like a community center. It is like the Drop-In Center Part 2; people come over, they eat, we have fun and we play games. Because people expressed that they wanted [that space]. Everyone is allowed just to be as they are.

JH: It’s too easy to move through your job or your life and not be thoughtful. You are asking people to be thoughtful and practice those little acts of care. I want to end by asking you about how you are caring for yourself, how you are replenishing?

KM: One big step, I started therapy last month. I am getting monthly massages. We have to be intentional about that, we need rest, we need breaks. I am trying, I have improved.