On Abstraction: Things You Can't Tell Just by Looking at Us

Within this text, you’ll find the makings of a new series called The Flow, where contributors are invited to create call and responses between artworks, art movements, or artists with another outlet or field they have an existing relationship with. This is an exercise in expanding entry points and access for appreciating and connecting to works of art and artists by seeing art from multiple vantage points and perspectives. An audio recording is available at the bottom of this text; please follow along.

A note: This piece has been heavily hyperlinked. If you see a bolded, a bolded italicized, or an underlined word within a section, please click it.

Fact: Figurative works post well on socials.

A Confession

It all began out of frustration. I attended a fine arts high school in Birmingham, Alabama, as a Visual Arts major, where we were required to take a survey art history class in our junior year. Each student was assigned a specific work of art to write a report on. Willem de Kooning’s Woman I (1950–1952) was given to me. Now some folks may have considered the pairings as arbitrary, but from a young age, I’ve tended to read more deeply into things. I believed the picks were intentional, as most of the pairings referenced the student’s styles and interests. Except glaringly, for me. Looking at Woman I, I was repelled by the figure represented. At the time, I was creating flat, patterned, technicolored Matisse inspired self-portraits and interiors. In hindsight, it wasn’t what he depicted but how he depicted that I needed to see: the gestural brushstroke, the impastoed paint application, the emotive colors, the loosely rendered figure that blended in and emerged from its environment. It was learning how jazz music directed the movement and rhythm for so many Abstract Expressionist works—I’d been listening to a cd of my Mom’s on repeat since freshman year called Great Ladies of Jazz (1995).

Later that year, I did away with the human figure and started painting surrealistic landscapes with barren red trees1. But I hit a wall. Tired and frustrated by trying to ‘depict’ something and not knowing what else to do, I slashed my canvas, draped a plastic tarp over it, and walked away. Then my teacher, Mr. Neel, came by and said, “Those shadows are nice.” The shadows were from the sunlight peeking through the slashed parts of the canvas. I began to paint the shadows themselves. Eventually, I did away with the painted on front-facing plastic tarp and focused on building out the skeletal frame. The tarp had become a holdout, a means of trying to retain a direct link to the physical act and constructs of painting. The frames had become a reconstruction or a redaction of painting. I manipulated them by attaching whatever material called to me from the aisles of hardware stores, leaning into the material’s texture, color, weight, and malleability. I was intrigued by the prospect of someone who knew their intended function questioning why they were being used in this manner and if that changed their perception of them. I constructed hybrids with intentional lighting that expanded the shadows and stretched the shapes beyond the rectangle and square, consuming more space than I could physically reach or occupy.

Side Note

I’m leaning into introspection. In this time of remoteness, I have engaged in numerous Q&A sessions with myself. An ongoing work in progress of trying to unpack, sort through the baggage, and revisit, reflect on the mementos that build up a life, this life. And in the clearing of the clutter, be in a position to understand and affirm what I believe in, why I believe in it, and how to make the best use of all that I’ve collected, absorbed, and inherited. I’m letting you into the inner workings of my process.

I moved into Abstraction because figuration became an ill-fitting mask to hide behind. If I wasn’t yet comfortable in my own body, how could I properly depict her? Or maybe it was just that my peers didn’t relate to my figures and I took it too personally. If only I had seen the work of Bob Thompson or Benny Andrews or Faith Ringgold or Alice Neel or Emma Amos or Beauford Delaney2. Maybe I wouldn’t have felt so defeated amongst a class of Minimalists, European Impressionists, and Conceptualists—Silence is a killer in critiques. The figure felt like an extended roadblock, where I idled until a new direction opened. My pivot was drilling holes, getting splinters, stapling mesh, lace, and moldings. I was bending screen and chicken wire, threading electrical wire, and knotting rope. I didn’t care that my hands were being cut up and roughened because I liked the rawness, the frayed edges, the un-polished-ness of it all. I liked the possibility that the work was a touch hazardous if you didn’t pay attention. That its space was a deception: where did the frame end and the shadows begin? I savored the labor of it all and created intuitively. So, if you asked me “the why,” I couldn’t tell you. Because perhaps at that time, I didn’t fully know. Was I subliminally connecting to my great grandmother’s patchwork quilts? Referencing the doorways and decaying shotgun houses we’d pass in the car near Legion Field? The window screens to keep out the mosquitoes? Was it a Southerner's play on De Stijl?

Maybe I just valued the physicality of the process of making and working through my questions more than finding an answer through a perfectly resolved artwork. The parts of the whole were not precious and only possessed a shimmering aura because of my pursuit of some functional transfiguration3. Because once I left for college and my mom wanted to reclaim parts of the house, they became a warped and discarded heap of building materials at the mercy of the elements — just a pile of wood, wire, rope, and screen. Looking back, some twenty years later, I was a dreamer who wanted to imagine new spaces, create new and expansive environments in response to the limitations of my current surroundings4. These frames were self-portraits. Abstracted manifestations of a young Black female body perpetually questioning and navigating her (in)visibility, her existence, her agency, and ownership in and of space. I didn’t yet have a tangible vocabulary—I was channeling. A conduit engaged in a psychic conversation with makers I didn’t know existed yet. I didn’t know that down I-20W / I-59S, so many kindred souls had been born, and one, in particular, had long gone up North before I was a figment in my parents’ minds.

Question: So how do you define abstraction (which is broader and more expansive than the Abstract Expressionism movement)?5

Answer: I’ll start with what it is not. I do not see it as a reduction or a simplification. I see it as an exploration. I view it as an explosion and expansion that pushes mediums, materials, objects, persons, places, and things to their limits, free from certain constraints of representation into their pure beings and spirits of selfhood. The figure acts as a stand-in for the viewer, directing the flow and reading of the work depending on the angle, framing, viewpoint, and perspective the artist provides us. Abstraction removes the barrier to entry and brings the viewer in direct engagement with the artist’s thoughts and visions. Your read, your experience is dictated by what pulls you in. And let’s be clear non-representational (form/physical) does not equal not representing (concept, event, object). New vocabularies are developed, new glossaries necessary that are distinctly defined by the artist and not by pre-existing social, cultural, critical expectations, or norms. I’m thinking of how we often talk in terms of (object)ive or (subject)ive, but maybe there needs to be a third and a fourth and a seventh term for perspective. And we have time now, so much time. Now’s a great time to lean into and linger.

Planting Seeds (we’ll come back to this)

An Ode to Jack Whitten: I went to sleep thinking of you, woke up thinking of you, January 2018 The sites/sights you captured / I knew / [beat] / Remember / those smoke stacks / that towered above and around us / the monoliths of steel of iron of forge / of Bessemer of Ensley of Bombingham / that Enveloped us / in a haze of / Clouded abstractions / clogging bleeding thickening / the air / Emblazoning / the night / skies / with superficial glows and hues? / The fire / Yours a time of segregation / Mine a time of / integration / And yet / And still / We both got away / You got away got away followed the star(s) / I got away got away followed / that same star(s) / that same call / [beat] / Your name / didn’t give you away /Your hand / didn’t give you away / {things you can’t tell just by looking at us} / Your titles / were the codes the clues the signs the symbols the shoutouts the throwbacks the elegies the memorials the hymns and the beats / that I could crack / that I could read / that enveloped me enveloped me / Led me into / our shared histories / [beat] / Black man Black man / wandering East Village streets / Later / Black girl Black girl / wandering wandering those same same / East Village streets / Looking looking / Found the path you’d traced and etched and scratched and spread and dropped and built out and smeared and stained and dragged / the decades the decades the decades / Before / I made it there. / I was a painter / Didn’t you know? / I was a historian / Didn’t you know? / Wish I’d wish I’d known You / Then / Seen you seen You / Then / then Connected the dots Then / then / then when I Fell / in love with AbEx / they didn’t tell me about / You or Alma or Norman / DeKooning DeKooning / was all / they knew / Didn’t affirm / Didn’t acknowledge / That Black folks / We too / see in / feel in / love in / paint paint paint fucking paint / in abstraction / with the exception that / We sure do / Play play play / in grooves of abstraction / You knew that too / [beat] / They probably knew if / [beat] / I would have followed You / [beat] / Now / Approaching You / no first names / Please / I Revert to / the Etiquette / To excuse me / To Mr / To Sir / To I’m from down the road from You / Native son, Native daughter / so honored / so honored / to meet You.

A Glossary

Growing up, whenever I asked my Mom the meaning of a word, she would say look it up and I’d go find the dictionary or use context clues or familiar parts of the whole word to make sense of it or I’d make it up. [smile]

| Define | looking | Define | material | Define | representation |

| Define | seeing | Define | sublime | Define | non-representational |

| Define | feeling | Define | origin | Define | composition |

| Define | relating | Define | appropriation | Define | love |

| Define | interpretation | Define | literal | Define | emotion |

| Define | imagination | Define | normalize | Define | expression |

| Define | invisible | Define | structure | Define | avant-garde |

| Define | visible | Define | color | Define | experimentation |

| Define | improvisation | Define | space | Define | deconstruction |

| Define | conceptual | Define | political | Define | reconstruction |

| Define | realism | Define | occupation | Define | construction |

| Define | social realism | Define | liberation | Define | migration |

| Define | abstract expressionism | Define | autonomy | Define | somatic |

| Define | modernism | Define | communication | Define | embodied |

| Define | figuration | Define | mastery | Define | disembodied |

| Define | intuition | Define | gesture | Define | semiotics |

| Define | observation | Define | freedom | Define | glossolalia |

| Define | perspective | Define | formalism | Define | pareidolia6 |

Define: Black7

Question: What is it about Southerners, Black Southerners, particularly, and abstraction? Have our bodies been so at the forefront of physical pain and labor that creative expression courtesy of abstraction is our means of psychic freedom by way of de-robing, displacing ourselves of our earthly targeted and weighted bodies? That we walked into the river and emerged as free souls, absorbing dissolving, embedding ourselves into the atmospheres?

Charles Alston (Charlotte, NC) Ed Clark (New Orleans, LA) Thornton Dial (Emelle, AL) Leonardo Drew (Tallahassee, FL) Melvin Edwards (Houston, TX) Lonnie Holley (Birmingham, AL)8 Sam Gilliam (Tupelo, MS) | McArthur Binion (Macon, MS) Noah Purifoy (Snow Hill, AL) Alma Thomas (Columbus, GA) Jack Whitten (Bessemer, AL) William T. Williams (Cross Creek, NC) Betty Blayton-Taylor (Williamsburg, VA) |

Answer: Abstraction emerges from all regions and time zones. But I believe the nuances of abstraction are dictated by the environment by circumstance by a people. And as a native Southern daughter, what I feel in my bones is dictated and shaped by red soil by Black Belts by steel plants by white columns by silent forests by churning factories by unwavering faith by a constant and dogged fight for a better life. In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois witnessed how “In those sombre forest of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself,—darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another.”9 Southern Black Abstraction derives from an adaptation for survival—in this space, we are safe to say and do. That attaining a place looks like rejecting a system you were born into, full of omission of oppression of repression whether you were knowingly cognizant of the confines or not. That being oneself looks like not being tied down to a Eurocentric gaze and standard. That power looks like creating by feeling by intuition by envisioning futures not yet tangible and resetting presents that include oneself and one’s people. That mission looks like leaning into and trusting the patterns and rhythms and forms and lines and palettes inherited through apprenticeships through D.N.A.s through divine interventions. That revelation looks like knowing we are merely vessels of higher forces, utilized to communicate and testify. We were mastered, then we mastered, and then we defied. In abstraction, we could carry messages that those who didn’t have the key wouldn’t be able to decipher. In the same ways that Negro spirituals offered comfort and navigational routes to the North and safe houses. In the same way, worn clothes became patchwork quilts that kept us warm, and provided a visual archive and a family history when reading and writing were illegal. In the same way, as “Bless your Heart” offers sweetness and sass. We create worlds within worlds to be free.

Setting the Tone

In college, I was an art history major as well as a docent in the school’s gallery. I wanted to be a connector and a translator between and for the artist, the art historian, and the multitude of publics. For a late-night program, each docent was tasked with creating a presentation for artwork from the collection. The abstract works tended to intimidate groups the most. And so, liking a challenge, I selected Hans Hofmann’s painting Au Printemps (1955).

Question: What’s in a name?

Answer: A goldmine, an open door, a starting point, a flashlight.

As I spoke, student musicians played jazz in the background. I hoped the music would act as a blanket to envelop and warm up the viewers from the perceived coldness of the white canvas occupied by long smears, loose squiggles, and quick dabs of warm and cool hues. And it did. Once they connected to the sonic rhythm and grooves, the visitors threw off the blankets, their muscles relaxed and opened up. They were ready to consume, to connect to a canvas that before had seemed stagnant, intimidating but had slowly become alive and inviting, blossoming before their eyes into an immersive tableau of springtime.

Will you join me now for such an engagement?

The FLOW

Remember when I planted seeds earlier? We’ve returned to them. I’ll now guide you as we fertilize and cultivate the garden of art appreciation.

Deep Readings (A Visual and A Sound: A Three Course Pairing + A Treat )

Prompt: Ready? Please take my hand. We’ll wash before and after if you’re daring. Otherwise, let’s spread ourselves out. I’d like to walk you through this. At whatever pace feels comfortable, feels right. Take your time.

Supplies: Something to write with, Something to write on, Something to sit on (comfortably for an extended period of time).

With each pairing, click on the bolded and italicized artwork and song titles to view and to listen.

Each course provides a time commitment dependent on your stamina and appetite to engage.

1

Estimated Time: 6 mins

First: Take a look at Howardena Pindell's, Feast Day of Iemanja II, December 31, from 1980 for about a minute in silence.

BUT, do not read the text underneath the image!

Second: Play Manha de Carnaval (Eurydice) from Black Orpheus (1959).

For the duration of the song, just look at the work, soaking it all up like a sponge, allowing the music to give you a beat to move across and through it, to breathe with it.

But wait: If your memory’s like mine, it’s okay to start taking notes while you’re listening.

Next: When the song concludes, close your eyes. What do you remember?

Then: Write down all that you saw (the colors, textures, materials), all that you felt (the temperature [of the materials, the colors, the textures], literal and metaphorical weight of the work, emotional reactions, tone) and all that you thought (personal, collective, historical memories, and reactions).

Finally: Take a look at the artwork label.

PAUSE

before you click, before you press play

A Consideration

"If I want to improvise during “ Mary Had a Little Lamb,” for example; first I memorize it. That’s because when I’m performing on stage, I want to let my mind be completely free. “Mary Had a Little Lamb” is there, and I can come back to it if I want, but what I’m creating is greater than the sum of the parts — technical ability, notes, themes — I’ve collected along the way. The song is in the back of my brain, where many other things are stored, and in that way, it becomes just another item that I can call upon when I’m playing. The spirit of art shines through in a performance when I stop thinking — when I let the music play itself, not just the one song that I’ve memorized, but all of the songs and experiences I have in my mind. And as things come to me, unplanned, I surprise even myself.”10

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANNNNNNNNNNNDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD GO!

How’d that go for you?

Question: Are the people who like jazz the ones who like abstraction? Are the people who like jazz, not the ones who like abstraction? Are the people who don’t like jazz the ones who like abstraction? Are the people who don’t like jazz the ones who don’t like abstraction?

Answer: I’ve attended several talks, overhead multiple conversations where people will mic drop, and the conversation moves on by just saying: “The Undercommons.” In this case, I’m going to add, In the Break, and keep it moving.11 Although, there is one thought I’d like you to sink into: the potential for the creator in both jazz and abstraction to emote what Fred Moten describes as an “internal exteriority of a voice which is and is not his own.”12

2

Let’s try that again

Estimated Time: 10 mins

First: Melvin Edwards, Cotton Hangup, 1966

Second: Max Roach’s Driva’ Man from WE INSIST! Freedom Now Suite (1961)

Next: Take it in

Then: Process & Reflect

Finally: Review

A Palette Cleanser

At a reading for Rutgers University’s English Department in 2018, the poet Will Alexander said [paraphrased from my notes]: “Don’t listen to the words, listen to the sounds underneath—don’t break it into the parts.”

So what would that mean for abstract (visual) art? If words don’t go here either. What would it mean to listen for or to “see” the sites/sights underneath?

3

The main course

Estimated Time: 15 mins

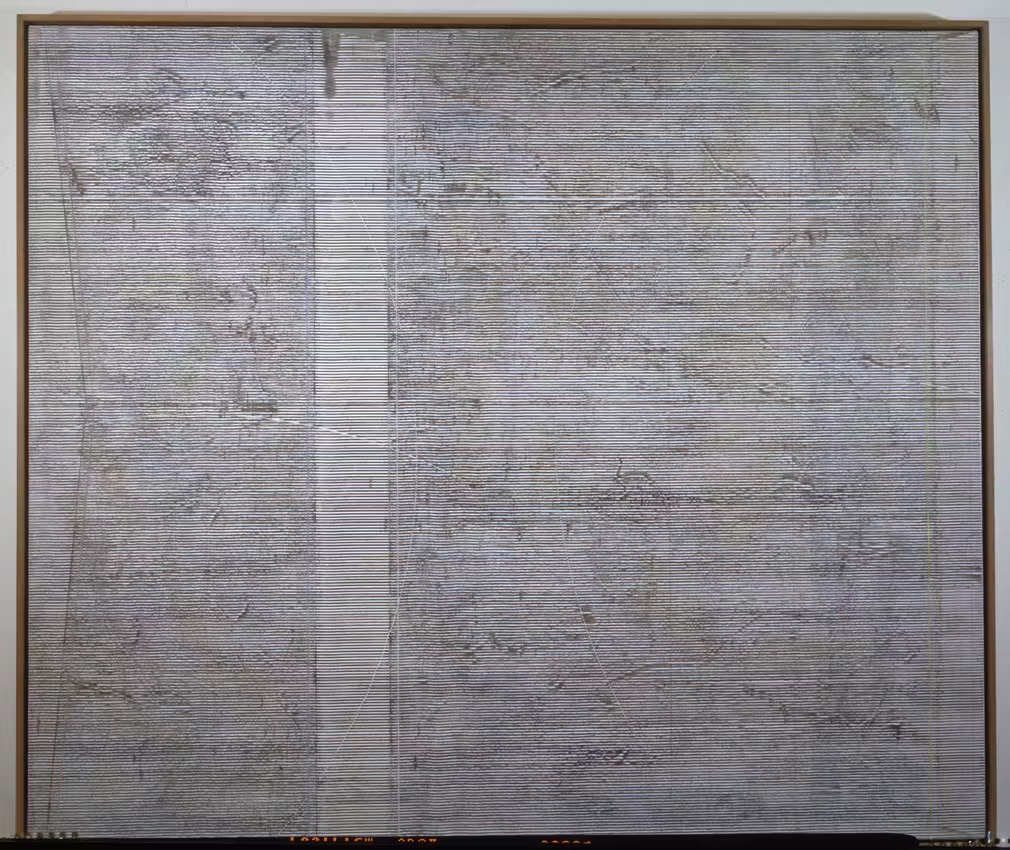

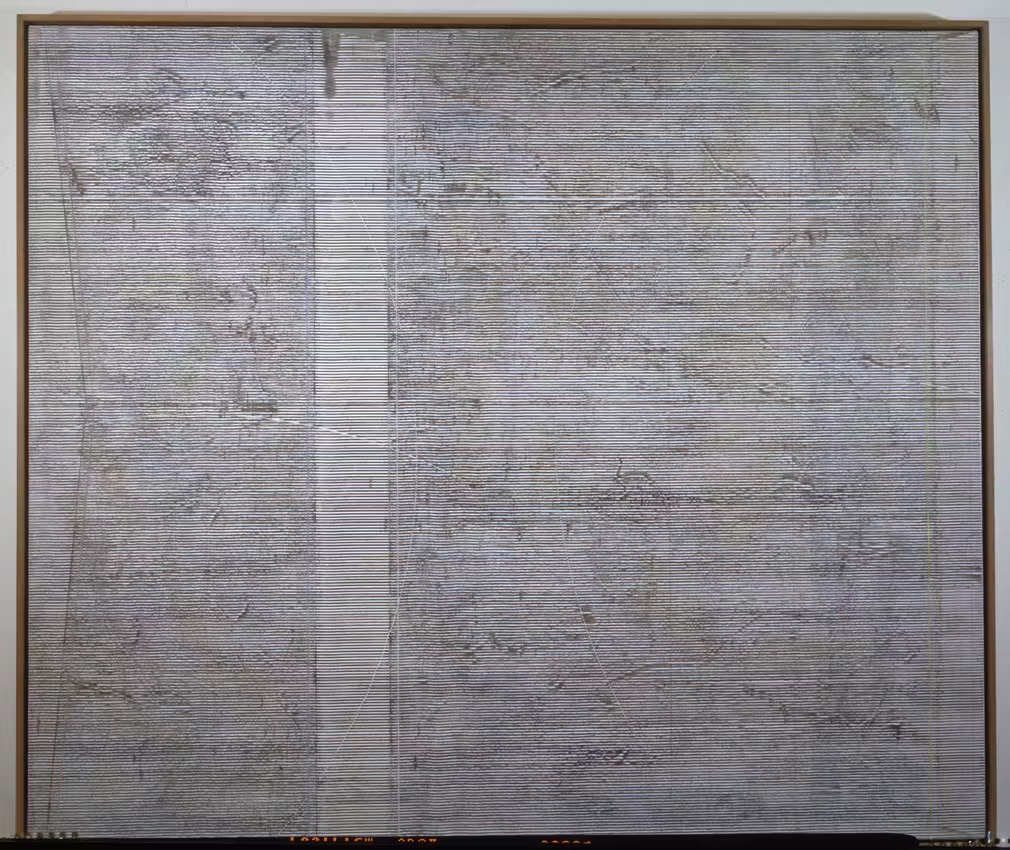

First: Jack Whitten, Khee I, 1978

Second: Miles Davis’s Pharoah’s Dance Part 1 from Bitches Brew (1970)

Next: Take it in

Then: Process & Reflect

Finally: Review

A Complimentary Dessert

(It's the difference from loving somebody and being in love with somebody)

Well, you tell me. What’s the difference?

(Okay, You can love anybody but when you’re in love with somebody you’re looking at it like this: You’re taking that person for what he or she is no matter what he or she look like or no matter what he or she do)

(You’re crazy! You fall in love, you can fall out of love)

(You might stop being in love but you are not gonna stop loving that person)

(Maybe they ain’t never been loved before or been in love before, they don’t know what the feeling is to be loved)

(She poetic)14

4

And one to grow on

Estimated Time: 8 mins

First: Chakaia Booker, Repugnant Rapunzel (Let Down Your Hair), 1995

Second: Black Star’s Astronomy (8th Light) from Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Blackstar (1998)

Next: Take it in

Then: Process & Reflect

Finally: Review

The Artist’s Voice

Once a work leaves the safety of the studio, artists can lose control of how their works are read. Whatever the original intention, meaning, message, or narrative of a work, it can be shifted, altered, misinterpreted, or affirmed depending on the beholder’s tools, baggage, and experiences. As a gesture to reclaim the creator’s power, click on an artist’s name below and hear about their practices from the artists themselves.

Jack Whitten

Howardena Pindell

Melvin Edwards

Chakaia Booker

An Abbreviated Acknowledgement of Abstraction

(Selections from the Permanent Collection and artists featured in past exhibitions) Now, explore on your own. Click any of the links below to view works and articles to create your own wall label, poem, or musical pairing:

Charles Alston / Hurvin Anderson / Romare Bearden / Kevin Beasley / McArthur Binion / Betty Blayton-Taylor / Frank Bowling / Mark Bradford / Peter Bradley / Michael Bramwell / Charles Burwell / Nanette Carter / Barbara Chase-Riboud / Ed Clark / Gregory Coates / Leonardo Drew / Torkwase Dyson / Rico Gaston / Ellen Gallagher / Sam Gilliam / Cynthia Hawkins / Richard Hunt / Suzanne Jackson / Steffani Jemison / Daniel LaRue Johnson / Jennie C. Jones / Jacob Lawrence13 / Norman Lewis / James Little / Al Loving / Kori Newkirk / Eric Mack / Richard Mayhew / Julie Mehretu / Harold Mendez / Rodney McMillian / Senga Nengudi / Odili Donald Odita / Martin Puryear / Mavis Pusey / Thomas Sills / Shinque Smith / Kianja Strobert / Alma Thomas / Stanley Whitney / William T. Williams / Hale Woodruff

Selected Exhibitions

Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction 1964-1980, The Studio Museum in Harlem, 2006 Blackness in Abstraction, Pace Gallery, 2016 Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction 1960s to Today, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017 Solidary & Solitary: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection, Nasher Museum, 2018 What Music is Within Black Abstraction from the Permanent Collection, Ogden Museum, 2020

Bibliography + Additional Resources

William Arnett, “Interviews with Thornton Dial”, Souls Grown Deep, 1995-1996. Manuel Arturo Abreu, An Alternative History of Abstraction, May 16, 2020, Atlanta Contemporary Chloë Bass, "Can Abstraction Help Us Understand the Value of Black Lives?”, Hyperallergic, July 28, 2016 John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1972) Kevin Beasley, Instagram post, Sept 17, 2020 Rika Burnham and Elliot Kai-Kee, Teaching in the Art Museum: Interpretation as Experience (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2011) Steve Cannon, Quincy Troupe, and Cannon Hersey, “Peter Bradley”, Bomb, January 17, 2017. Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016) Ben Davis, “Yes, Black Women Made Abstract Art Too, as a Resounding New Show Makes Clear”, Artnet News, October 20, 2017. W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk, (New York: Signet Classic Edition/Penguin, 1995) Adrienne Edwards, “Blackness in Abstraction”, Art in America, January 5, 2015, Expo Chicago, Dialogues: Curatorial Forum Presents: Out of Body | Black Identity in Abstraction with Valerie Cassell, Naomi Beckwith, and Romi Crawford, Sept 21, 2017. Molly Glentzer, “Just listen: The minimalist art of Jennie C. Jones”, Houston Chronicle, January 8, 2016 Lauryn Hill, "Outro from “Doo Wop (That Thing)", The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, 1998 Monique Long, “Torkwase Dyson tells the history of Black liberation through cartographic art”, Document, Sept 27, 2019 Louis Menand, “Unpopular Front”,The New Yorker, October 10, 2005. Fred Moten, “The Sentimental Avant-Garde,” In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 25-84 Fred Moten, “Blackness and Nonperformance”, Afterlives, MoMA LIVE, Sept 25, 2015 “The Black Artist in America: A Symposium [Romare Bearden, Sam Gilliam, Jr., Richard Hunt, Jacob Lawrence, Tom Lloyd, William Williams, and Hale Woodruff]”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 27, No. 5 (Jan. 1969), pp. 245-261 Seph Rodney, “How to Embed a Shout: A New Generation of Black Artists Contends with Abstraction”, Hyperallergic, August 23, 2017 Sonny Rollins, “Art Never Dies”, The New York Times, May 18, 2020 Giovanni Russonello, “Jazz Has Always Been Protest Music. Can It Meet This Moment?”, The New York Times, September 3, 2020 Hilarie Sheets, “The Changing Complex Profile of Black Abstract Painters”, ArtNews, June 4, 2014 Melissa Smith, “‘We Had to Do It For Ourselves’: Legendary Gallerist and Artist Suzanne Jackson on Why the Art World Has Never Gotten Her Story Right”, Artnet, November 20, 2019, Roberta Smith, “The Radical Quilting of Rosie Lee Tompkins”, The New York Times, June 29, 2020 Mildred Thomas, “Interview with Emma Amos”, Artpapers, March/April 1995 Victoria L. Valentine, “Culture Talk: Curator Adrienne Edwards on Her New Exhibition ‘Blackness in Abstraction’", Culture Type, July 5, 2016 David Wallace, “Fred Moten’s Radical Critique of the Present”, The New Yorker, April 30, 2018

Endnotes

1 At the December 2019 Lea K. Green Artist Talk, honoree Dawoud Bey said [paraphrased from my memory]: Even when the figure is absent, the figure is present.

2 Beauford was a last hurrah discovery courtesy of an Essence Magazine article that included one painting. I can’t find the article but given the timing of when I saw it, I believe it was reference to the traveling exhibition,”Beauford Delaney: The Color Yellow," curated by Richard Powell. (2002-2003)

3 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” (1935)

4 In addition to the actual frames, I would create what could now be viewed as crude architectural hand-drawn renderings of existing and yet realized frames.

5 Louis Menand, Unpopular Front, The New Yorker, October 10, 2005

6 Yes, Jose, I can see it. I can see so many things. It’s a face, it’s a constellation.

7 Thank you, Malcolm.

8 Lonnie was referred to as The Sandman growing up.

9 Du Bois, 49

10 Sonny Rollins, Art Never Dies, The New York Times, May 18, 2020

11 Is anyone up for another reading group/book club/study group?

12 Moten, 38

ƒ13 Shout out to Esteban del Valle, who asked the question: Why do you know, how do you know it’s a pool table with players around it? We’re pulling from existing references of what we know to be familiar, similar. Our conversation was around this Lawrence piece.

14 Lauryn Hill, "Outro from "Doo Wop (That Thing)," The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, 1998

&

One more for the road

Estimated time: a lifetime

David Hammons's Abstract Crashing: First Movement (1980) with

Joe McPhee’s Nation Time,1970