Love and Refusal in the Art of Juliana Huxtable, Texas Isaiah, and Toyin Ojih Odutola

My fascination with art arose from an abyss of theoretical and existential curiosities relating to love, the complexities of a Black diasporic identity, and academic training versus lived experience. As these queries surfaced, swelling in size and intensity, I consoled myself with the concepts, materials, and substance of artists who offer renewed perspectives. Artists then became “my access to me… my entrance into my own interior life.”1

From this opening, I will explore the idea of “truth” as derived from notions of love and refusal. To do so, I’ve engaged the practices of Texas Isaiah (T.I.), Juliana Huxtable, and Toyin Ojih Odutola, whose works live within and outside of the permanent collection at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and wherein I discovered a rejection of dominant codes and cultures in favor of imagined and functional possibilities. The ensuing works by these artists expose the tensions and oppositions embedded in our present circumstances, challenging viewers to reconcile these opposites so as to arrive at a locus of “truth” and, perhaps, love.

First, I would like to share definitions of “love” and “refusal.” Applying scholar bell hooks’s idea of choosing to love and “act in ways that liberate ourselves and others,”2 along with her citing of M. Scott Peck, I will adopt “love” as “the will to nurture our own and another’s spiritual growth,” and treat it as “an act of will … both an intention and an action.”3 As a cooperative feat, love includes both the self and the participant, the artist and the observer—love is personal yet social and communal. While hooks’s philosophy on love transcends racial categories, Tina Campt’s theorizing of refusal emerges from a deep looking with and study of a “black visuality” executed by Black contemporary artists who make viewers work by “creat[ing] radical modalities of witnessing that refuse authoritative forms of visuality which function to refuse blackness itself.”4 Their creations demonstrate what Campt defines as “refusal”: “A rejection of the status quo as livable and the creation of possibility in the face of negation.”5 To live beyond “the terms of diminished subjecthood with which one is presented,”6 might engender transformation and liberation. Moreover, to separate oneself from the ascribed properties of one’s identity can be an act of refusal. Perhaps then, refusal is analogous to the process of coming back to oneself, to one’s true nature—to love!

Texas Isaiah's (T.I.) photographic series “My Name is My Name” (2016) combines self-portraiture and altar-making (the placement of ephemera that invokes the spirit of oneself and one’s ancestors) to draw connections to selfhood, protection, rituals, nature, and spirit-work (the act of communing with oneself or one’s ancestors). Situated in a light-filled room with khaki-colored walls, the artist sits nude on hardwood floors in the photograph My Name is My Name I (2016). T.I.'s body coils, his head bows and tucks between his knees. With outstretched arms, the artist's clasped hands face the ground. To T.I.'s right lies a large and slightly drooping evergreen plant that arches over his frame and onto another withered potted plant. A window casts cool morning light into the room, to anoint this scene as serene and sanctified. In a position of prayer or meditation, the artist’s still body tempts a viewer’s quietude. One should approach the image with care.

T.I.’s oeuvre stimulates questions relating to self-communion and a return to one’s nascent existence. Within the artist’s statement is a fruitful query: “How can we navigate protection when we are creating portals of openness?"7 The artist’s strategy of self-protection might explain his decision to refuse a viewer’s mutual gaze in My Name is My Name I. T.I. is both physically and spiritually wrapped up in himself, and as viewers, we bear witness to this moment of rest and respite. Rather than taking part in the participatory act of looking between subject and viewer, the viewer’s gaze falls instead on the artist’s body. T.I.’s self-portrait aptly aligns with Campt’s invitation that we must listen to the image and “listen to the infrasonic frequencies … that register through feeling rather than vision of audible sound.”8 Passaging with the artist through his private healing space, I considered T.I.’s refusal of spectatorship in this display of self-care and self-intimacy. Perhaps T.I.’s rupture of a participatory gaze and provocation for the viewer’s participation in spirit-work/altar-work offers an opportunity to see oneself by digging deep, for “when we unblock our despair, everything else follows—the respect and awe, the love.”9

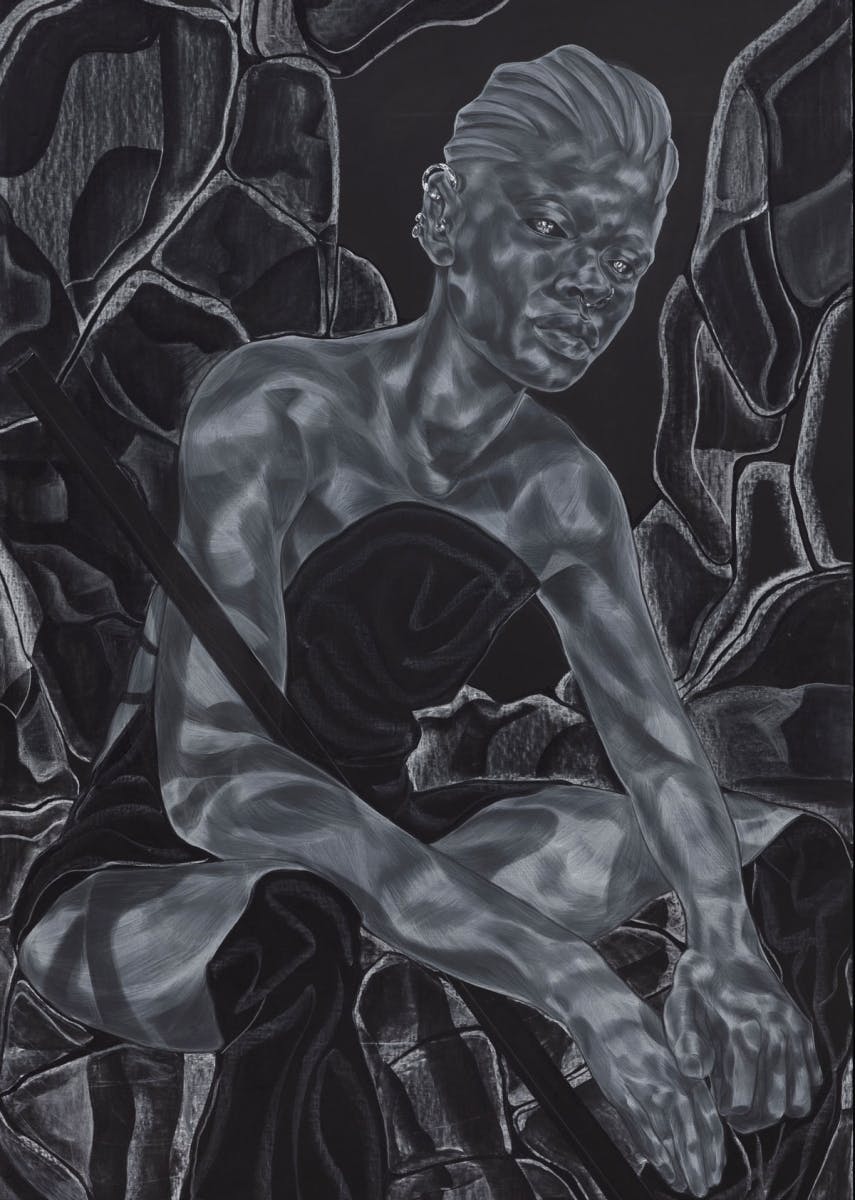

On the topic of listening, Toyin Ojih Odutola’s The Listener (2021; previously on view at Frick Madison March 31–September 11, 2022), quite literally shut me up. The work’s monumentality—its size and positioning on the wall—towered over my slim frame and lobbied for my attention. Placed among a group of oil paintings by Rembrandt hung Odutola’s drawing in charcoal, pastel, and chalk on linen over black Dibond panel. Seated, I scanned over the elaborate rendering of a woman warrior who I recognized as a female member of the Eshu tribe in the artist’s epic of an imagined prehistoric civilization. Nestled within large rock formations, the character rests her elbows on her knees with a staff-like object latent at her right forearm. Over-the-knee boots and a strapless garment cling to her frame so as to pronounce her combatant build. The artist adorns the figure with slicked-back cornrows, ear and nose jewelry, and a piercing gaze. Her glistening pupils emit a shimmering and celestial reflection, accomplished by daubs of white and gray color. The work’s entire composition evinces the artist’s command of grisaille, or the execution of varying tones of gray to achieve a sculptural illusion.

Though not confirmed, The Listener resembles the figure of Akanke from Odutola’s visual narrative, “The Tale of Akanke and Aldo.” Organized by the Barbican Centre, and later traveling to the Kunsten Museum of Modern

As a cooperative feat, love includes both the self and the participant, the artist and the observer—love is personal yet social and communal.

Art Aalborg and the Smithsonian’s Hirschhorn Museum, the artist’s solo exhibition A Countervailing Theory featured forty drawings to illustrate the fictitious world where Akanke and Aldo reside. Inspired by the ecoregion of central Nigeria’s Jos Plateau, Odutola’s imagined environment conjures a prehistoric civilization that bespeaks a role reversal: warrior women (Eshu) rule over humanoid male laborers (Koba) and heterosexual relations are illegal.10 This flipping of patriarchal gender roles, albeit alluring, still delineates a system of domination and inequality, supremacy and fugivity, and mastery and servantry. Odutola countervails the general imperialist dynamic by positioning Black women as captors. As tasteful as this reversal might seem, Odutola’s narrative exemplifies Audre Lorde’s proclamation against the use of the master’s tools.

Isolating The Listener within “The Tale of Akanke and Aldo,” Odutola presents a representation of what could be Akanke at the story’s turning point: when Aldo confesses the system’s unfair hierarchy to Akanke, and articulates how they might conceive a more just reality. Akanke then promptly “does the unthinkable: she listens, comes to terms with her own position within the system and eventually agrees.”11 Aldo’s refusal to remain silent and Akanke’s listening—her resonance with this revelation—activates a deepened love and trust between the two, shaping “the basis for structural disruption.”12 Can Odutola’s decision to silence Akanke harness an appetite for hearing the unseen? Perhaps listening is a courageous act of “ripping the veil,”13 exposing that which is hidden.

Visual and performance artist and DJ Juliana Huxtable presents a unique fashioning of refusal in Untitled (Casual Power) (2015). By means of an all-caps lavender typeface, Untitled (Casual Power) is both prose and social commentary. The text begins with “IF YOU WALK UP THROUGH HARLEM AND ALONG THE BRONX RIVER,” and proceeds to envisage “A MYTHICAL LAND” where “BLACK UNICORNS RUN FREELY.” Myriad references evoke pop cultural events and American colonial history. Certain words appear more legible, and others are awash against the abstracted background, visualized as an abyss of orange, violet, and shades in between. The text, justified in layout, blurs against the dizzying backdrop and commands a new reading framework—one that discriminates against legibility and grips obscurity. Huxtable’s text refuses conventional methods of reading comprehension: the ability to process text, understand its meaning, and connect with known beliefs or experiences. Instead, Untitled (Casual Power) jolts one into the unknown. What if in this space of uncertainty and wonder lies beauty? What if, as the work suggests, you began a sentence with no predetermined topic, or charted a path with no foreseeable destination?

What if you fervently trusted in the efficacy of your own curiosities? Untitled (Casual Power) may just encourage a rejection of trying to figure things out, to quit behaving and acting like you know what’s up, and for you to discover the unfamiliar and the untouched. Embedded within this refusal of making/meaning is an undoing of self and a surrendering to beauty, wonder, and love, for “when we love we are changed utterly .... We sacrifice our old selves in order to be changed by love and we surrender to the power of the new self.”14

Refusal is an act of love and love is an act of refusal as both processes enact a change of (and return to) self. Both, as well as the act of looking itself, require the consistent choice to stay still enough to recognize and unravel discomfort in order to grasp, with tenacity, a perspective of one’s truth.

Notes

1) Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998), 95.

2) bell hooks, “Love as the Practice of Freedom,” Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations (New York: Routledge, 1994), 250.

3) bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (New York: William Morrow, 2000), 4–5.

4) Tina Marie Campt, “Black Visuality and the Practice of Refusal,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 29, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 79–87, doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2019.1573625.

5) Ibid.

6) Ibid.

7) Texas Isaiah, “My Name is My Name,” Artist’s Statement, 2016.

8) Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 52.

9) Joanna Macy, World as Lover, World as Self: Courage for Global Justice and Ecological Renewal (Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 2007), 95.

10) Toyin Ojih Odutola, “The Tale of Akanke and Aldo.” Text reproduced from Lotte Johnson, ed., Toyin Ojih Odutola: A Countervailing Theory (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 2020).

11) Ibid.

12) Ibid.

13) Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” 91.

14) bell hooks, All About Love, 188.