Ideal Selfie

What if I told you that at heart, artist Qualeasha Wood’s art practice is tied to her life-long commitment to being a troll?

Qualesha Wood, 2021-22 artist in residence

Raised in South Jersey by a Christian family, Wood’s childhood cultural references were diverse —by the age of ten, she had read the Bible in its entirety, was listening to Bruce Springsteen and Bon Jovi, and knew she was a lesbian, a dirty word in the 2000s. She understood she didn’t fit in her white New Jersey suburb as a young alternative Black gay girl. And as much as her mother tried to keep her offline, Wood learned early on she could embody a version of herself who could resist being outcasted or judged on the internet. Creating digital avatars and role-playing on platforms like Neopets, Runescape, and the video game The Sims, Wood found kindred queer and alternative communities. Now, the twenty-seven-year-old artist knows better than most that the internet is a place where one can become their ideal self, often to a fault. This knowledge has undeniably shaped her practice.

Once in college, Wood used online platforms to define herself. “On Facebook, by developing a profile, I felt like I was developing a personality,” she explains. “I really didn't get active on Facebook until I went to college, a time when I was turning over a new leaf in my life. I was like, ‘I want to be popular, I want to be more social, I want to be more outgoing.’ A big part of that was building a Facebook presence that showed I was those things.” Already a very online person, she used Facebook to construct her online reputation as a meme queen and artist while studying printmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design, becoming hypervisible online. A proud double Scorpio, popularity has always come naturally to Wood.1

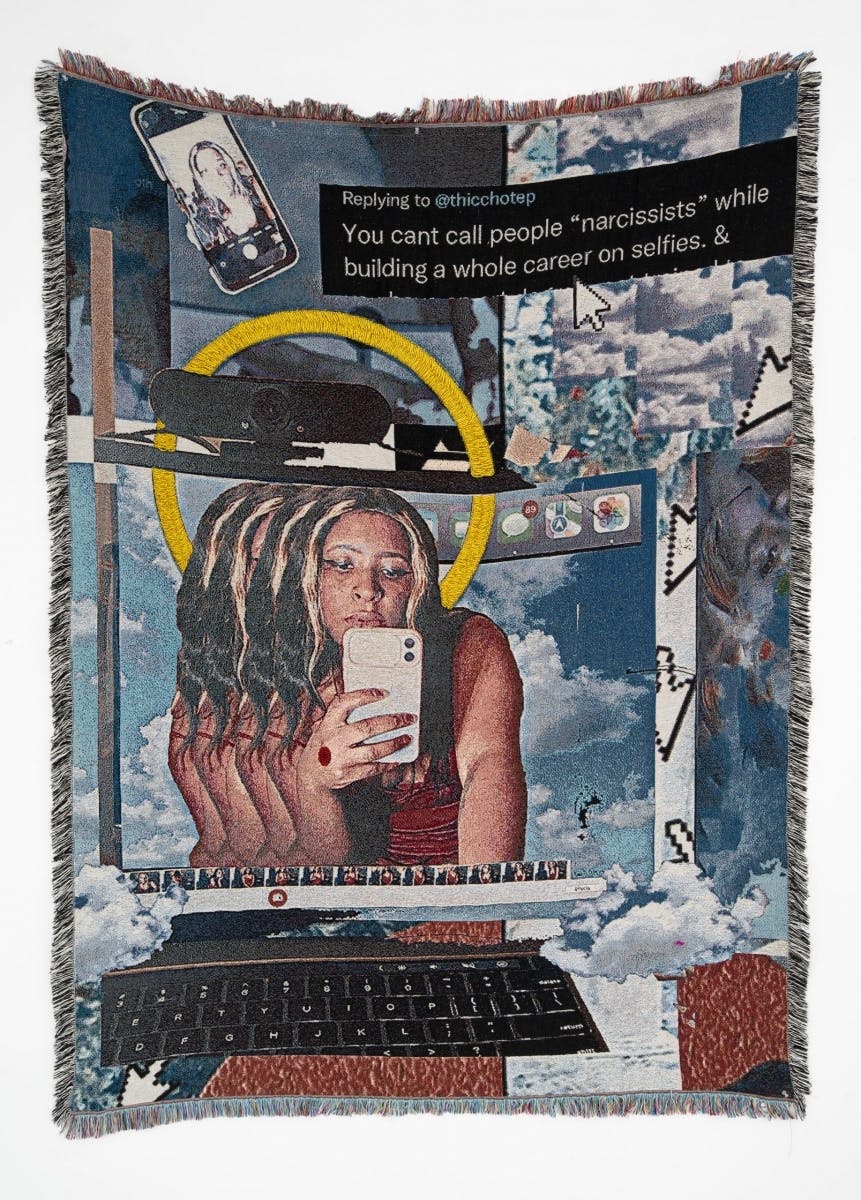

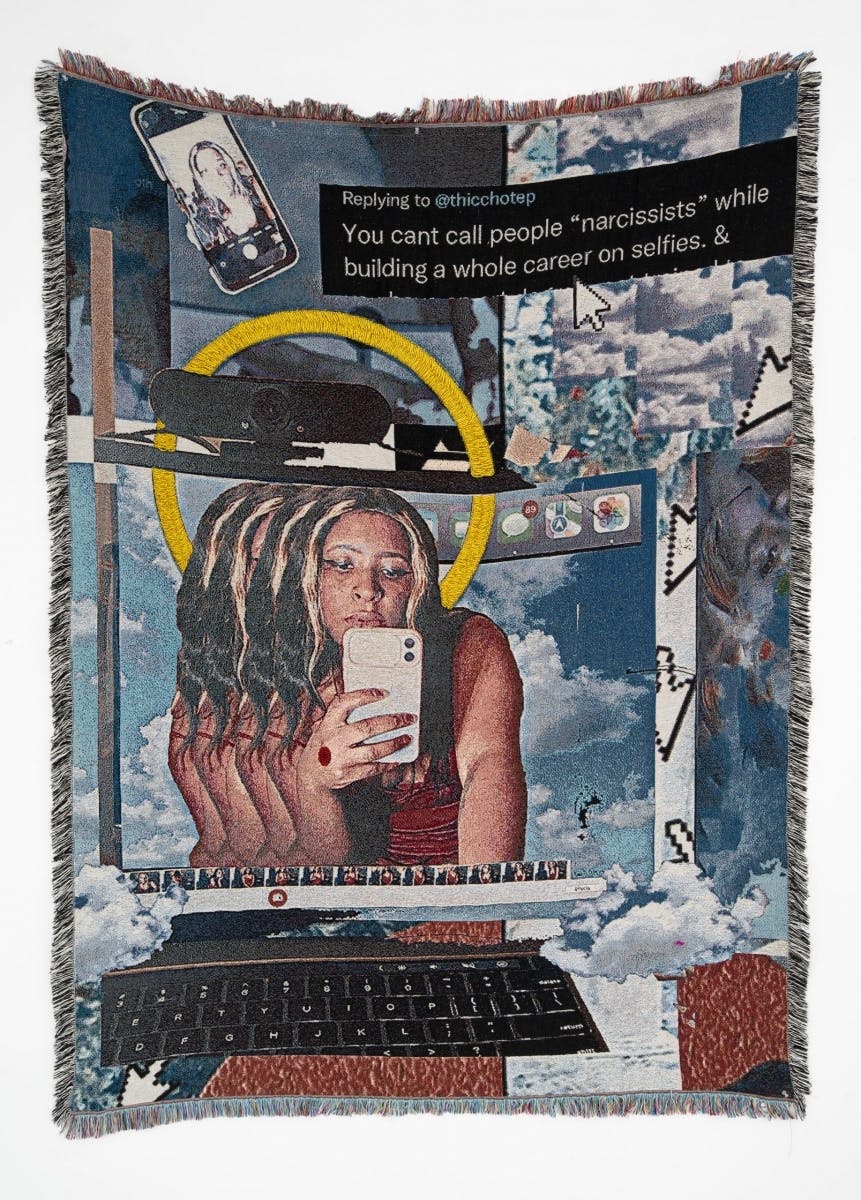

Since 2018, her time online and desire to project an idealized persona threads through fantastical and iconoclastic woven self-portraits. In her tapestries, she references everyone from Michelangelo to Cardi B, drawing inspiration from Christian iconography, Renaissance painting, cyberfeminism, meme culture (which is notably Black), and Black femme culture.2 Within these compositions, she casts herself as the central figure, imaging herself in her signature red dress in her bedroom in Photo Booth selfies adorned with screenshots of iMessage exchanges, Tweets, and emojis that provide visual narrative. Wood asserts control over the surveillant webcam, which remains a permanent fixture throughout the tapestries. The medium itself, Jacquard tapestry, offers a pixelesque effect, while the artist uses glass seed beads as embellishment for halos, crosses, stigmata, and whatever else transcends the mundane. These tapestries act as not only a window into Wood’s desktop screen, but her ineffable self-image.

By situating herself as a Black femme messiah, a self-created world order emerges; the work is devotional. In Error404 (2022), Wood gazes down upon the webcam’s eye, and the viewer. The image is set against a heavenly blue sky (like the Windows 98 desktop wallpaper); a halo band of glimmering glass beads, encircles her, doubly serving as a gilt mirror frame. Duplicate “fatal error” pop-up messages appear, reading “Warning, can’t load fetishization. Please try again in 30 seconds.” A large pixelated cursor hovers over the retry button—a reminder to come for her correctly. The work is in part a response to her increased visibility online and offline; she talks about being doxxed for infiltrating a Tomi Lahren Facebook group and unrelatedly experiencing increased sexual projections from strangers, even unsolicited requests for her to perform as a dominatrix. For Wood, religiosity, then, becomes a stage for both self-love and self-defense, from the haters and whoever else threatens her self-image, her autonomy, her practice. “[The work is] no longer a debate between white Jesus or Black Jesus. I've made that decision; it's me in this moment, and it can be any Black femme who wants to step into that power,” she explains. To this end, the works almost feel made for an altar. These dynamic multilayered compositions offer a narrative entirely unique to her own very real creation myth.

“I definitely developed a God complex when I was playing The Sims,” she says.

Still, Wood is not a narcissist. As an online young adult, Wood once felt treated by many of her peers like an internet messiah, which she reminds me is not the same as being a role model. In fact, she prefers it less. She reflects: “I realized the internet is a cult, and I think everyone, in a way, is a cult leader. Your followers reflect that, people agreeing with your posts reflect that. I realized people began to treat me like this internet messiah.” In part owing to this awareness, her practice uses her likeness, as she’s hyper-aware of how visible she is, how surveilled she’s been. The text in Cult Following (2018) reads “God is a young hot ebony and she’s on the internet,” evoking the “young hot ebony” online ads often soliciting some form of virtual sex work, and further critiquing how Black femme bodies are represented as sexualized commodities online, a click away from consumption. A more recent tapestry, ‘FOREVA’ by Cardi B (2021), titled after a Cardi B song, immortalizes an online feud she had with a noted Twitter critic and hater. “You can’t call people narcissists while building a whole career on selfies,” her critic writes in a screenshot of a Tweet. Her self-portraiture consciously subverts oppressive digital structures, emphasizing how prosaic online interactions have the potential to serve as acts of violence against representations of the Black queer feminine body online. While she can’t control how her image is consumed, with the work, she can control how she is seen. (She admits she’s a bit of a “control freak.”)

Wood has many (correct) hot takes. She relishes defying tradition and exceeding expectations. When discussing her approach to textile work more broadly, she tells me that “labor is overrated,” with the reasoning that “from a capitalist perspective, work is literally valued for how much people think you put into it.” For this, she’s been heavily criticized for her identification as a fiber artist, since she doesn’t hand-weave her tapestries. “With craft, people care about how you did it, but I was most interested in the why. Even though I don't want to be a part of every part of the [weaving] process, I do love the process. And I love the results more than anything else.” This motivation in the why explains her interest in challenging the people she doesn't like—Marcel Duchamp, and any other white men or theorists who have been given a false authority over the scope of what constitutes art and media. This tension between what’s considered craft and what’s considered art, kitsch, and what gets placed in a museum, has fueled her subject matter. As such, many of her past work’s titles subversively reference the Bible or the work of other white men—Genesis (2021)—theorists such as Sigmund Freud—The [Black] Madonna-Whore Complex (2021)—in pursuit of an intervention in dialogues long dictated by dead white men. She isn’t interested in making anyone comfortable, but she is interested in taking up space.

Her recent series of tufted works turn inward to a more vulnerable inner child, offering meditations where her Jacquard tapestries boast declarations. Recalling interior domestic spaces and carpeted play areas from childhood, her tufted works arise from Wood’s past. She began working with tuftings in 2020, shortly after finding an old family photo of her childhood bedroom at her parent’s house in Long Branch, New Jersey. In the photo, a vintage Looney Tunes rug, meant for the floor, was pinned to her wall above her crib. In thinking about her family’s generational familiarity with craft as a domestic resource and tool, tufting became an obvious choice for her to expand her practice. “It wasn't about labor, but it was about finding a way to reconnect with the process,” she says. “[It’s about] people of color and queer people who have used craft historically, to make things, to survive, and [who] don't try to make millions of dollars off of it,” she continues, remembering how her grandmother crocheted blankets to keep family members warm.3

Using a chromatic range of yarn, she began to tuft silhouetted Black figures in vivid scenes that drew on traumatic memories. The tuftings, also self-portraits, are inspired by the visual aesthetic of cartoons like Looney Tunes, or Tom & Jerry, recalling the Black minstrelsy within early cartoons—her figures notably only feature wide eyes (and occasionally bright red nipples) onto which the whites of the eyes, which also resemble the Eyes emoji, starkly contrast the black color of the figures’ bodies. While the figure’s expressions are rather ambiguous, allowing the work to function as an emotional Rorschach test, they impart a deep sense of surveillance, and as a consequence, for Black audiences, fear.4 They are a commentary on how Black femmes are both surveilled and are conscious of ever-present surveillance online and offline.5 “What if someone had a real conversation about identity politics or moments of blackness in this medium?” Wood questioned. Motivated by the lack of critical work she saw pushing the boundaries between craft and fine arts, Wood’s tuftings continue to earnestly consider how race, surveillance, and power shape Black experience, especially in childhood.

In It’s time for me to go: Studio Museum Artists in Residence 2021–22, we see Wood’s characteristic keen conceptual wit at work in the tufted medium. Primary colors and hot pinks are swapped for dark monochromatic compositions. The works present a moment not fixed in time, and the figures’ surroundings, painted in greyscale, offer personal memories shrouded in shadows, the color of darkness, black. The scale of these tuftings dwarfs her past work. Key to this body of work are the same cartoon eyes we see throughout her past tuftings, a device she uses to reflect our own gaze, and remind us of the gaze we might be under. In Familiar Strangers (2022), the figure’s eyes are mirrored in its shadow—is Wood referring to the omnipresent gaze we might feel on us in the dark as a young child, online, or in the world as a Black woman? Or to her self-directed gaze? The title points to the latter. Sometimes our reflections are the most familiar of strangers. Accordingly, Wood shares that the tufted works offer a meditative space for her inner child. She’s working through the past in real-time. She tells me she wants all of her work to stand the test of time. “I want people to look back at my work [from any point in time], and be able to think, ‘Wow, she was crazy.’” An iconic, and iconoclastic, but no less honest desire.

If a troll is someone who consciously shares provocative, controversial ideas or “hot takes” in aims of provoking a response or manipulating an audiences’ perception, Woods is a masterful internet troll, retaining control over her narrative, while pulling all the strings. Qualeasha Wood makes it look effortless.

NOTES

1) In writing on Scorpio placements in astrology, writer and astrologer Alice Sparkly Kat has said, “[double Scorpios] have real influence and [they] do not have the need to show it off because [their] followers do the flexing for [them]. Later the astrologer says that individuals with Wood’s astrological placement’s “influence comes from [their] control of how people desire [them] and how [they] desire others.”

2) The use of (Black) memes in popular culture is discussed as a site of mass digital appropriation and exploitation by artist and theorist Aria Dean and writer and critic Lauren Michelle Jackson. The appropriation of memes, and by extension, Black labor is contextualized by a history of consumption and "theft" of blackness.

3) The New Bend, a group presentation curated by Legacy Russell (former Associate Curator of Exhibitions at The Studio Museum in Harlem) in which Wood’s Ctrl+Alt+Del (2021) was included, shares this thesis. Drawing on the work of the quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, the show explores how craft traditions have been expanded upon by artists of color, such as Wood.

4) Personally, Wood’s use of the eyes as a visual device reminds me of Daniel Kaluuya’s performance in Get Out. In both bodies of work, the eyes convey fear, give a great deal of narrative insight, and offer a characteristically Black point of view.

5) Simone Brown’s work in Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness speaks to how blackness is a site through which surveillance is practice, developed, and rooted.