A Collection is Born

The Studio Museum in Harlem opened in 1968—a watershed year that included the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, major anti–Vietnam War demonstrations, Tommie Smith’s and John Carlos’s Black Power salutes at the Summer Olympics, the publication of Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, the murders of several members of the Black Panther Party, and the police riot against protestors at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago—amid larger discussions of the struggles of disenfranchised peoples around the world and the place of Black artists in the art world.1 The Museum’s founders were a diverse group of artists, activists, and philanthropists all committed to creating an institution in Harlem that foregrounded the role of artists and education, especially during such a tumultuous moment in US history.

Activism among African-American artists increased dramatically in the years leading up to the establishment of the Studio Museum. The artist collective Spiral, originally formed in New York City in 1963 to discuss the organization of a bus to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, met regularly until 1965 to address both members’ work and pressing social issues.2 The Harlem Cultural Council, founded in 1964, provided arts programming for the community, with culturally specific arts organizations including the Dance Theater of Harlem opening in the following years. In addition, the 1965 founding of the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School by the poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) in Harlem is widely considered to have formally established the Black Arts Movement, a flourishing of Black cultural production in the visual arts, theater, literature, and poetry in the 1960s and 1970s.3 Coinciding with the founding of these institutions was the New York Public Library’s threat to close the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the fall of 1968 and the growing discussions around the planning and organization of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s controversial 1969 exhibition Harlem on My Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968.4 In November 1968, the Harlem Cultural Council, whose members included artists Charles Alston, Romare Bearden, and Bruce Nugent, formally withdrew its support of Harlem on My Mind, citing a “breakdown in communications” and the emphasis on entertainment rather than culture.5 The Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) was formed directly in response, raising public awareness of discriminatory practices in the art world through public demonstrations and meetings.6 These social, political, and art-world upheavals set the stage for the Studio Museum’s opening in September 1968.

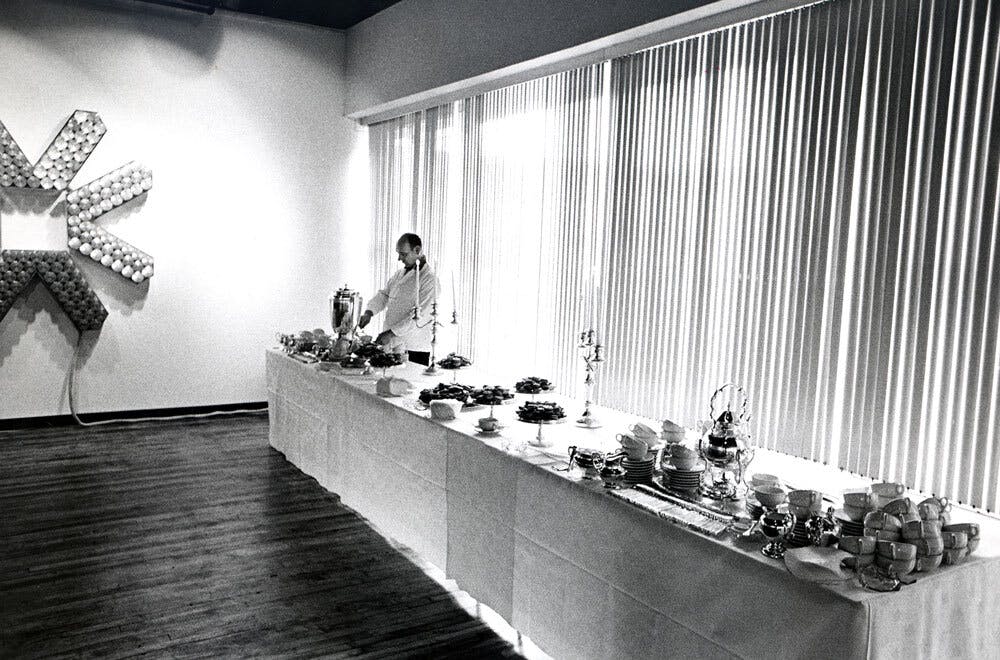

The Museum’s inaugural exhibition, at its rented loft on Fifth Avenue just north of 125th Street, was a solo show of Tom Lloyd’s electronically programmed light sculptures. The exhibition, Electronic Refractions II, was the first project of the Museum’s Studio Program, in which the institution underwrote the cost of materials to create new works, engaged young apprentices to assist the artist, and showcased the resulting works in an exhibition. Inspired by flashing traffic lights and theater marquees, the sculptures used both everyday materials, such as Christmas lightbulbs and plastic Buick headlight covers, and industrial materials provided by Alan Sussman, a technical consultant who was an engineer at the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). The works, with names taken from racehorses and entirely programmed by Lloyd, received generally positive critical reviews but mixed ones from the public.7 According to Edward S. Spriggs, who became the Museum’s Director in July 1969, it was too early to be showing Lloyd’s work in Harlem. On opening night, a man verbalized his anger that the Museum was not a “Black art museum” before damaging one sculpture, apparently upset that the works did not seem to be by a Black artist. It appeared that “Harlem had spoken and was saying that you cannot just bring anything you want to Harlem and press it on us anymore.”8

Shortly before his exhibition opened, Lloyd had participated in a panel at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized in an attempt to quell early dissatisfaction with Harlem on My Mind. During the panel, Lloyd frequently clashed with several other panelists, including Sam Gilliam, William T. Williams, and Hale Woodruff, on the definition and importance of “Black art.”9 For Lloyd, his work was “Black art” because he was an African-American artist thinking about his community and making his sculptures accessible to that community, something that was perhaps more visible in the process of making rather than in the actual works. While many Black artists at the time struggled with the desire to divorce their artistic practice from their political views, Lloyd strongly felt that “art, as far as possible, should be inter-connected with political and social action.”10 The disagreements among the artists on this panel reflect the diversity of opinions about what it meant to be a Black artist working in the United States at the time. The Studio Museum’s early exhibition history reflects these multiple points of view: Invisible Americans: Black Artists of the 30s (1968), organized in response to a Whitney Museum of American Art survey that omitted works by Black artists; Afro-Haitian Images and Sounds Today (1969), which included works by thirty artists as well as Haitian music, documentary slides, and reconstructions of two vodou altars; A Photographic Essay on the Black Panthers (1969), organized by the de Young Museum with photographs by Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones; X to the Fourth Power (1969), featuring work by Melvin Edwards, Gilliam, Steven Kelsey, and Williams; and Harlem Artists 69 (1969), an exhibition that celebrated the work of artists living in the community.

These exhibitions demonstrate the Museum’s ambitious mission, expressed in the prospectus that was printed at the beginning of the annual report for the inaugural year: “The arts can help our cities and the people who live in them to a wider comprehension of human needs. We must learn to understand the great capacity of art to communicate across all manner of human boundaries, not just the lines that divide the past and the present but that separate one way of life and one spirit from another.”11 In its first year, the Museum exhibited shows that reflected on the local community, the national political moment, and an African diasporic artistic presence, and spoke against dominant art-historical narratives. It was originally conceived as a space to create opportunities for both artists to make and exhibit new works and the general public to become involved in contemporary art. Interestingly, in the press leading up to the Museum’s opening, it was announced that “the museum has forsworn a permanent collection, a traditional feature of art museums” in order “to maintain the flexibility by this dual objective,” since “meeting new needs requires a free-wheeling approach, which could, in its view, be impeded by a vested interest in any artist or art style.”12

The Museum had an advisory committee of artists, educators, and critics including Benny Andrews, Elizabeth Catlett, David Driskell, Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, and Woodruff—who all agreed that building a collection was imperative.

Thus, the Studio Museum did not begin as a collecting institution. For Eleanor Holmes Norton, then–vice president of the Museum, “When you have the vested interest of a collection, you lose the desire to innovate. We’re trying to do something other museums aren’t. We want to show new work that the older establishments aren’t on to. And of course that includes artists of all ethnic groups.”13 The gift of Eldzier Cortor’s The Room by a private collector just three years later, then, is surprising.14 Several gifts of works on paper had been accepted by the Museum in 1970, thereby establishing the fledgling collection just two years after the institution’s founding. These gifts, though, were all made by the artists themselves, who were in their twenties and early thirties—over two decades younger than Cortor—and thus the institution’s target demographic. All made around 1970, the works were also politically engaged, most of them explicitly commenting on the status of African Americans in contemporary US society. The Room, painted twenty years earlier, spoke to a different, albeit no less fraught, time. Although the collection now includes works from the early nineteenth century to the present, the painting remained an anomaly within the collection until the late 1970s, when a 1951 landscape by Loïs Mailou Jones was gifted to the Museum.

For the first several years of its life, the Museum actively resisted collecting in order to adhere to its original concept as a working space for living artists, even as it continued to accept gifts of works of art. While the idea of a radical, avant-garde space was commendable, it had to shed most of that identity in order to respond to the immediate needs of its community of Harlem, thus becoming a fine arts museum.15 It was not until 1977, almost a decade after its founding and when Mary Schmidt Campbell became Director, that the institution stated a change in its collecting policy. The year before, the Museum had established the Curatorial Council—an advisory committee of artists, educators, and critics including Benny Andrews, Elizabeth Catlett, David Driskell, Jacob Lawrence, Norman Lewis, and Woodruff—who all agreed that building a collection was imperative.16 Many other artists also encouraged the Museum to collect as a way to preserve works of art. With this new focus on the collection, the Museum quickly recognized the need for a permanent facility, rather than the space it had been renting since its founding. Two years after the establishment of a collection policy, the New York Bank for Savings donated its former home on 125th Street between Lenox and Seventh Avenues to the Museum.

By the end of the Museum’s first decade, well over one hundred works had been gifted to the collection, including a painting by Betty Blayton-Taylor, a museum founder, and several works on paper by both Bearden and Catlett. The collection, however, more than doubled within the next five years as a result of the excitement around the move from the rented loft at 2033 Fifth Avenue to the permanent home at 144 West 125th Street. With the announcement of the acquisition of this site, the institution began to receive major gifts of works from private collectors, dramatically increasing the profile of the collection.17 At a prominent location in the heart of central Harlem, the new museum provided opportunities for larger exhibitions and programs and expanded storage space, a necessity given the rapidly increasing size of the collection.

—Connie Choi, Excerpt from “Black Refractions” in Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem (New York: Rizzoli, 2019), 30–31.

1. For an introduction to similar contemporaneous international events, see Cynthia A. Young, “Civil Rights and the Rise of a New Cultural Imagination,” in Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, exh. cat. (New York: Brooklyn Museum; Monacelli Press, 2014), 109–18.

2. See Jeanne Siegel, “Why Spiral?,” Artnews (September 1966): 48–51, 67–68.

3. In the 1950s, LeRoi Jones associated with Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, co-edited the avant-garde literary magazine Yugen, and founded Totem Press. He published his first volume of poetry, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, in 1961. Following the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Jones moved to Harlem, founded BART/S, and became affiliated with the Black Power movement. He then moved to Newark in 1967 and changed his name to Imamu Amiri Baraka in 1968, the same year he co-edited Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing with Larry Neal.

4. For more information on and discussion of Harlem on My Mind, see Bridget R. Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011), and Susan E. Cahan, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

5. Grace Glueck, “Harlem Cultural Council Drops Support for Metropolitan Show,” New York Times, November 23, 1968, 62.

6. See Benny Andrews, “Benny Andrews Journal: A Black Artist’s View of Artistic and Political Activism, 1963–1973,” in Tradition and Conflict: Images of a Turbulent Decade, 1963–1973, exh. cat. (New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 1985), 69–73.

7. Alan Sussman, interview with the author, New York City, February 8, 2018.

8. Edward S. Spriggs, “Raising the ‘Studio’ at Studio Museum: Field Notes,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 29 (Fall 2011): 74.

9. See Romare Bearden et al., “The Black Artist in America: A Symposium,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 27, no. 5 (January 1969): 245–61.

10. Tom Lloyd, “Black Art—White Cultural Institutions,” in Black Art Notes, ed. and with introduction by Tom Lloyd ([1971]), 9. Black Art Notes began as a counterstatement to Robert Doty’s introduction in the catalogue of the Whitney Museum’s 1971 exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America.

11. The Studio Museum in Harlem 1968–1969 Annual Report (New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, n.d.), n.p.

12. “A Museum Is Born in Harlem,” New York Amsterdam News, September 21, 1968.

13. Norton, quoted in Grace Glueck, “A Very Own Thing in Harlem,” New York Times, September 15, 1968, 34.

14. The donor, Katrina McCormick Barnes, was from a prominent Chicago family and was described in 1945 as the “family rebel” who published “a leftist, internationalist monthly” after anonymously giving away $3,000,000. See “McCormick Weds,” Life 18, no. 2 (January 8, 1945): 38, and “Letters to the Editor: McCormick Wedding,” Life 18, no. 5 (January 29, 1945): 4.

15. Mary Schmidt Campbell, “Introduction: The History of Collecting at The Studio Museum in Harlem,” in The Permanent Collection of The Studio Museum in Harlem, Volume I, 1983 (New York: The Studio Museum in Harlem, 1983), 5.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid., 6.