Harlem Postcards Fall/Winter 2016–17

11.17.2016-04.02.2017

Harlem is about family and all of the many intertwined cultures that provide richness and texture. I redrew a Jazz Age–era typeface and added my own family and friends to the mix, including my ninety-six-year-old Aunt Pearl, who lived in Harlem when I was a kid. The art serves as a poster for both old and new Harlem, and makes a subtle nod to the neon signs that lit up clubs and theaters in days gone by.

As a child, I was taught that leaving a hat on the bed is unlucky, and that I shouldn't wear yellow. But I've always loved to swim in the summer style of New York’s street vendors, so when I saw this hat I couldn't resist.

In the winter of 2012 in Harlem, Zoe Buckman had a loaded encounter with a Hindu spiritual leader that prompted her to write a poem entitled “Swami-ji.” Here Buckman revisits the piece, but this time explores the relationship between sculpture and written text by superimposing an excerpt from the poem onto a gynecological examination table from the 1800s that she has reupholstered with vintage lingerie. This work is part of her ongoing series “Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable,” her response to the recent attacks on Planned Parenthood in the United States—attempts curtail women’s access to sexual health and their right to choice.

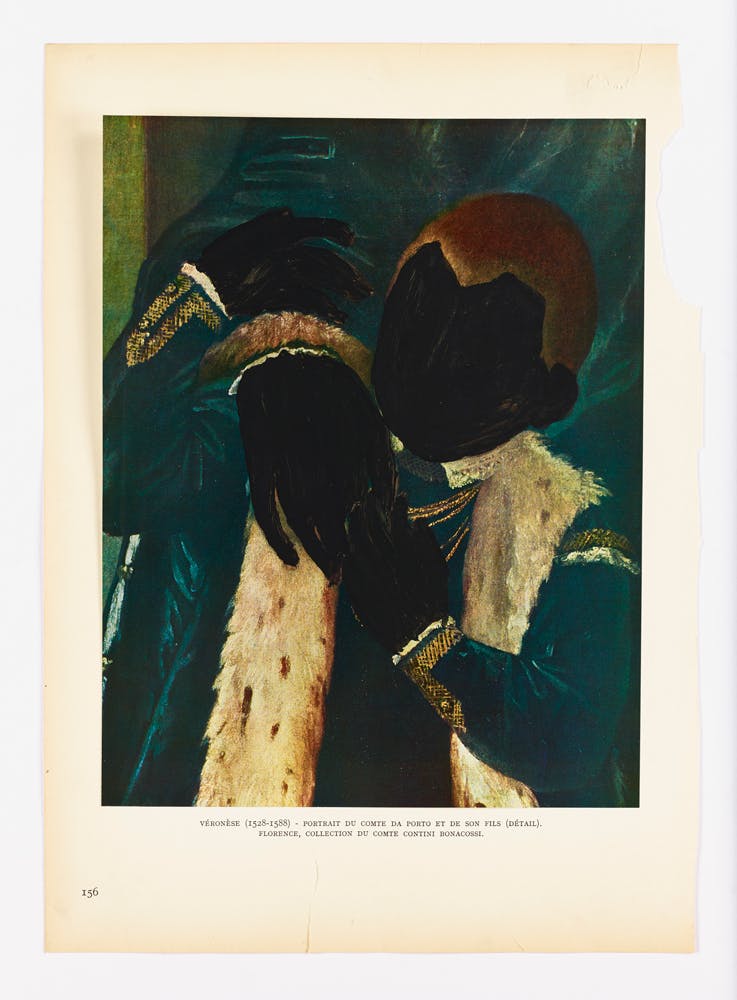

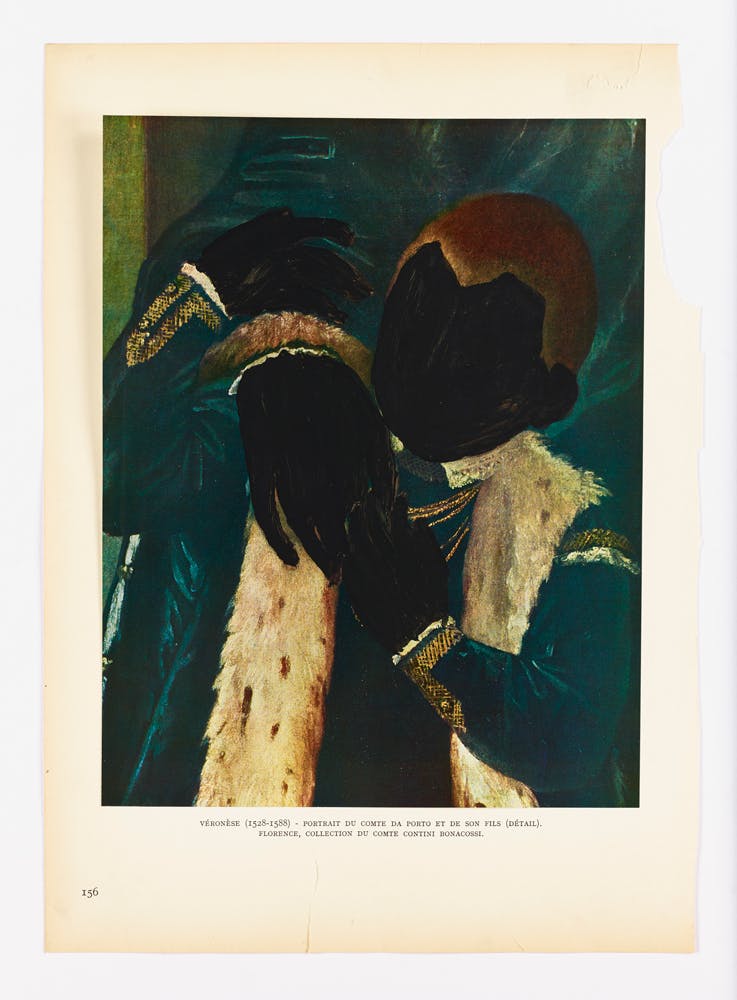

This work appropriates a detail of Paolo Veronese's 1552 Portrait of Count Giuseppe da Porto with his Son Adriano, which depicts both the loving embrace of father and son, as well as a Italian aristocracy and excess. Talwst's interest in Renaissance imagery stems from the erasure and whitewashing of Black historical figures such as Saint Maurice and Saint Jerome. In this work, the artist literally paints over the work of the great master to reclaim this violent act through a subversive gesture. The complete Blackness results in a total removal of the previous identity, but it is also an act of reclamation. The appropriated painting displays that positive images of white fatherhood have saturated the Euro-Western consciousness since the Renaissance. Today they are perpetuated and upheld by modern media. No comparable mainstream discourse exists with regards to Black fatherhood, which is too often depicted through damaging stereotypes. This work is inspired by the artist's own memories of weekends spent with his father. Thus he seeks to depict an alternative to the prevalent historical narrative through physically rendering the figures Black.

Harlem Postcards Fall/Winter 2016–17

11.17.2016-04.02.2017

Harlem is about family and all of the many intertwined cultures that provide richness and texture. I redrew a Jazz Age–era typeface and added my own family and friends to the mix, including my ninety-six-year-old Aunt Pearl, who lived in Harlem when I was a kid. The art serves as a poster for both old and new Harlem, and makes a subtle nod to the neon signs that lit up clubs and theaters in days gone by.

As a child, I was taught that leaving a hat on the bed is unlucky, and that I shouldn't wear yellow. But I've always loved to swim in the summer style of New York’s street vendors, so when I saw this hat I couldn't resist.

In the winter of 2012 in Harlem, Zoe Buckman had a loaded encounter with a Hindu spiritual leader that prompted her to write a poem entitled “Swami-ji.” Here Buckman revisits the piece, but this time explores the relationship between sculpture and written text by superimposing an excerpt from the poem onto a gynecological examination table from the 1800s that she has reupholstered with vintage lingerie. This work is part of her ongoing series “Mostly It’s Just Uncomfortable,” her response to the recent attacks on Planned Parenthood in the United States—attempts curtail women’s access to sexual health and their right to choice.

This work appropriates a detail of Paolo Veronese's 1552 Portrait of Count Giuseppe da Porto with his Son Adriano, which depicts both the loving embrace of father and son, as well as a Italian aristocracy and excess. Talwst's interest in Renaissance imagery stems from the erasure and whitewashing of Black historical figures such as Saint Maurice and Saint Jerome. In this work, the artist literally paints over the work of the great master to reclaim this violent act through a subversive gesture. The complete Blackness results in a total removal of the previous identity, but it is also an act of reclamation. The appropriated painting displays that positive images of white fatherhood have saturated the Euro-Western consciousness since the Renaissance. Today they are perpetuated and upheld by modern media. No comparable mainstream discourse exists with regards to Black fatherhood, which is too often depicted through damaging stereotypes. This work is inspired by the artist's own memories of weekends spent with his father. Thus he seeks to depict an alternative to the prevalent historical narrative through physically rendering the figures Black.